امپراتوری سلجوقی

امپراتوری سلجوقی،[8] حکومتی ترکتبار،[9][10][11] ترکی-ایرانی[12] و سنی مذهب بود که توسط ایل قنیق تُرکان اغوز بنا نهاده شد.[13] وسعت قلمرو سلجوقیان از شرق تا کوههای هندوکش، از غرب تا فلات آناتولی و شام، از شمال تا آسیای مرکزی و از جنوب تا خلیج فارس ادامه داشت. سلجوقیان سرزمین مادر خود یعنی حاشیه دریای آرال به خراسان حمله کرده و سپس وارد بخش مرکزی ایران شدند و پس از آن با پیروزی بر امپراتوری بیزانس در نبرد مَلازگرد، آناتولی را تصرف کردند.[14] سلجوقیان تحت سلطنت طغرل بیک، با ایجاد تسلط سیاسی بر خلافت عباسی در بغداد، رهبری جهان اسلام را به دست گرفتند.[15]

امپراتوری سلجوقی | |

|---|---|

| ۱۰۳۷–۱۱۹۴ | |

عقاب دو سر؛ نماد سلاجقه | |

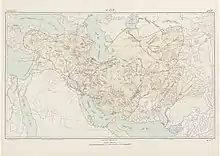

وسعت قلمرو سلجوقیان در سال ۱۰۹۲ (زمان مرگ ملکشاه یکم) | |

| وضعیت | امپراتوری |

| پایتخت | نیشابور (۱۰۳۷–۱۰۴۳) شهر ری (۱۰۴۳–۱۰۵۱) اصفهان (۱۰۵۱–۱۱۱۸) همدان، پایتخت غربی (۱۱۱۸–۱۱۹۴) مرو، پایتخت شرقی (۱۱۱۸–۱۱۵۳) |

| زبان(های) رایج | |

| دین(ها) | مسلمان سنی (حنفی) |

| حکومت | پادشاهی |

| سلطان | |

• ۱۰۳۷–۱۰۶۳ | طغرلبیک (اولین) |

• ۱۱۷۴–۱۱۹۴ | طغرل سوم (آخرین)[5][6] |

| تاریخ | |

• طغرل بیک آن را بنیان نهاد | ۱۰۳۷ |

| ۱۱۹۴ | |

| مساحت | |

| ۱۰۸۰ م. (تخمین) | ۳٬۹۰۰٬۰۰۰ کیلومترمربع (۱۵۰۰۰۰۰مایلمربع) |

| امروز بخشی از | |

جد این امپراتوری سلجوق پسر دقاق بود، دقاق بزرگترین فرماندهٔ نظامی ایالت اوغوز یبغو بود. به دلیل مهارت وی در تیراندازی به وی لقب تیمور یالیق (کمان آهنین) داده بودند.

امپراتوری سلجوقیان در سال ۱۰۳۷ میلادی توسط طغرلبیگ بنیانگذاری شد. طغرل به واسطه سلجوق بیگ که یکی از سران تُرکان اوغوز بود به قدرت رسید. سلجوقیان باعث اتحاد دوباره جهان اسلام شدند و نقش کلیدی در جنگهای صلیبی اول و دوم داشتند. سلجوقیان به شدت تحت تأثیر فرهنگ[16] و زبان[17] ایرانیان قرار گرفتند و نقش مهمی در ایجاد پیوند بین فرهنگهای ترکی-ایرانی بودند[18] به گونهای که حتی باعث انتقال فرهنگ ایرانی به فلات آناتولی نیز گشتند.[19][20] استقلال فرهنگی زبان فارسی (از زبان عربی) در امپراتوری سلجوقی شکوفا شد.[21] از آنجا که سلجوقیان، سنت اسلامی یا میراث ادبی قوی از خود نداشتند، زبان فرهنگی مدرسان فارسی خود در اسلام را به کار گرفتند، بدین ترتیب زبان و ادبیات فارسی در کل ایران رواج یافت و زبان عربی در آن کشور جز در آثار معارف دینی ناپدید شد.[21] مهاجرت ترکتباران به مناطق استراتژیک مرزهای شمالی و شمال غربی امپراتوری سلجوقی برای مقابله با حملات احتمالی دشمنان خارجی باعث ترکسازی این مناطق شد.[22]

سلاطین سلجوقی

| # | نام | فرمانروایی

(میلادی) |

زندگی

(میلادی) |

خویشاوندی | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| پادشاه | نام کامل | از | تا | زاده | وفات | ||

| ۱ | طغرلبیک | ابوطالب رکنالدین محمد | ۱۰۳۷ | ۱۰۶۳ | ۹۹۳ | ۱۰۶۳ | پسر میکائیل |

| ۲ | آلپارسلان | ابوشجاع عضدالدین محمد | ۱۰۶۳ | ۱۰۷۲ | ۱۰۲۹ | ۱۰۷۲ | برادرزادۀ طغرلبیک / پسر چغریبیک |

| ۳ | ملکشاه یکم | جلال الدوله معز الدنیا و الدین ابوالفتح حسن | ۱۰۷۲ | ۱۰۹۲ | ۱۰۵۵ | ۱۰۹۲ | پسر آلپارسلان |

| ۴ | محمود یکم | ناصرالدنیا و الدین محمود | ۱۲۰۰ | ۱۲۱۸ | ~ | ~ | پسر ملکشاه یکم |

| ۵ | برکیارق | ابوالمظفر رکنالدین برکیارق | ۱۰۹۴ | ۱۱۰۵ | ۱۰۸۰ | ۱۱۰۵ | پسر ملکشاه یکم |

| ۶ | ملکشاه دوم | معزالدین ملکشاه | ۱۱۰۵ | ۱۱۰۵ | ~ | ~ | پسر برکیارق |

| ۷ | محمد یکم | غیاثالدین محمد تپر | ۱۱۰۵ | ۱۱۱۸ | ۱۰۸۲ | ۱۱۱۸ | پسر ملکشاه یکم |

| ۸ | احمد سنجر | معزالدین ابوالحارث احمد سنجر | ۱۰۹۷ | ۱۱۵۷ | ۱۰۸۵ | ۱۱۵۷ | پسر ملکشاه یکم |

| سلطانهای ایران و عراق | |||||||

| ۸ | محمود دوم | مغیثالدین ابوالقاسم محمود | ۱۱۱۸ | ۱۱۳۱ | ۱۱۰۵ | ۱۱۳۱ | پسر محمد یکم |

| ۹ | داود | غیاثالدین داود | ۱۱۳۱ | ۱۱۳۱ | ~ | ۱۱۳۱ | پسر محمود دوم |

| ۱۰ | طغرل دوم | رکنالدین ابوطالب طغرل | ۱۱۳۴ | ۱۱۳۴ | ۱۱۰۹ | ۱۱۳۴ | پسر محمد یکم |

| ۱۱ | مسعود | غیاثالدین ابوالفتح مسعود | ۱۱۳۴ | ۱۱۵۲ | ۱۱۰۸ | ۱۱۵۲ | پسر محمد یکم |

| ۱۲ | ملکشاه سوم | معینالدین ملکشاه | ۱۱۵۲ | ۱۱۵۳ | ~ | ۱۱۶۰ | پسر محمود دوم |

| ۱۳ | محمد دوم | رکنالدین محمد | ۱۱۵۳ | ۱۱۵۹ | ۱۱۲۸ | ۱۱۵۹ | پسر محمود دوم |

| ۱۴ | سلیمانشاه | غیاثالدنیا و الدین سلیمان | ۱۱۵۹ | ۱۱۶۰ | ~ | ۱۱۶۱ | پسر محمد یکم |

| ۱۵ | ارسلانشاه | معزالدین ارسلان | ۱۱۶۰ | ۱۱۷۶ | ~ | ۱۱۷۶ | ~ |

| ۱۶ | طغرل سوم | ابوطالب رکنالدنیا طغرل | ۱۱۷۶ | ۱۱۹۴ | ~ | ۱۱۹۴ | پسر ارسلانشاه |

فرهنگ

سلجوقیان مراکز آموزش عالی را تأسیس کردند و حامیان هنر و ادبیات بودند. دستاوردهای علمی در دوران سلطنت آنها توسط دانشمندانی مانند عمر خیام و امام محمد غزالی مشخص میشود. در دوره امپراتوری سلجوقی، فارسی به زبان ضبط تاریخی تبدیل شد، در حالی که مرکز فرهنگ زبان عربی از بغداد به قاهره تغییر یافت.[23]بنیادگذاری مدارس نظامیه توسط خواجه نظامالملک طوسی در بغداد، بلخ، نیشابور و اصفهان از کوششهای فرهنگی این دوره است.[24] برنامه درسی نظامیه ابتدا به مطالعات دینی، قوانین اسلامی، ادبیات عرب و علم حساب متمرکز شده و بعداً به تاریخ، ریاضیات، علوم فیزیکی و موسیقی نیز تعمیم یافتهاست.[25]

امپراطوری سلجوقی، از نظر سیاسی و مذهبی، میراث محکمی را برای جهان اسلام به جا گذاشت. در دوره سلجوقی، شبکه ای از مدارس (دانشکدههای اسلامی) تأسیس شد که قادر به آموزش به مدیران دولتی و علمای دینی بود. در میان بسیاری از مساجد که توسط سلاطین سلجوقی ساخته شده بود، میتوان به مسجد بزرگ اصفهانی (مسجد جامع) اشاره کرد. استقلال فرهنگی زبان فارسی (از زبان عربی) در امپراتوری سلجوقی شکوفا شد. از آنجا که سلجوقیان، سنت اسلامی یا میراث ادبی قوی از خود نداشتند، زبان فرهنگی مدرسان فارسی خود در اسلام را به کار گرفتند، بدین ترتیب زبان و ادبیات فارسی در کل ایران رواج یافت و زبان عربی در آن کشور جز در آثار معارف دینی ناپدید شد.[21]

نویسندگان و مشاهیری مانند: حکیم عمر خیام، امام فخر رازی، امام محمد غزالی، ابوالفرج بنجوزی، شیخ شهاب الدّین سهروردی، امام الحرمین جوینی و امثال آنان نیز در این روزگار میزیستند.[26]

زبان فارسی در این دوره رواج کامل یافت و بیشتر پادشاهان سلجوقی در گسترش فرهنگ و تمدن ایرانی و سخن فارسی و تشویق و ترغیب شعرا و نویسندگان فارسیزبان کوشش فراوان کردند.

پادشاهان سلجوقی برخی خود شعر میسرودند، چنانکه ملکشاه سلجوقی هم اشعار فارسی حفظ داشت و هم خود به فارسی شعر میگفت و همچنین طغرل سوم آخرین پادشاه این سلسله شاعر فارسی گوی بودهاست.[27]

گروهی از شاعران این دوره همچون امیرالشعرا معزی، انوری و خاقانی و نظامی در شمار استادان و پیشکسوتان بزرگ شعر و ادب فارسی قرار گرفتند و سخنسرایان و نویسندگان دیگری که در این دوره از پشتیبانی شاهان و وزیران سلجوقی برخوردار بودند عبارتند از: ابوالفضل بیهقی، خواجه عبدالله انصاری، اسدی طوسی، حکیم ناصر خسرو، عمر خیام، سنایی، جمال الدین عبدالرزاق اصفهانی و دیگران… شعر فارسی در این روزگار پیشرفتهایی کرد و سبک ویژهای به نام سبک عراقی در آن پدید آمد.[27]

همچنین در دوران سلجوقی آثاری چون کتاب «الابنیه عن حقایق الادویه» در داروشناسی و مفردات دارو «زادالمسافرین» ناصرخسرو در حکمت نظری و «کیمیای سعادت غزالی در حکمت عملی به فارسی نوشته شدند؛ ولی کسانی چون زَمَخشَری و شهرستانی، نیز در این دوره کتب فراوانی به زبان عربی که در واقع زبان دینی بهشمار میرفت تألیف کردند.[27]

سلاطین سلجوقی به عنوان حاکمان اسلامی، در سراسر دوره حاکمیت خود، بر مذهب تأکید و تکیه داشتند؛ آنها حنفی مذهب بودند و همواره می کوشیدند تا وجهۀ مذهبی خویش را حفظ کنند.[28] آنها با توجه به نقشی که در جنگهای صلیبی داشته و فتوحاتی که در طول حکومت خود انجام دادند، سر جمع خدمت بزرگی را به جهان اسلام کرده اند. اسلام بخشی از گستردگی کنونی خود را مدیون تلاش ها،شجاعتها و از خودگذشتگی های این سلسله می باشد.

نگارخانه

تندیس علاءالدین کیقباد در آلانیا

تندیس علاءالدین کیقباد در آلانیا

سردیس یک شاهزاده دوره سلجوقیان

سردیس یک شاهزاده دوره سلجوقیان سکه شیر و خورشید نشان دوره سلجوقی

سکه شیر و خورشید نشان دوره سلجوقی امپراتوری سلجوقی

امپراتوری سلجوقی

جامع علاءالدین کیقباد در قونیه

جامع علاءالدین کیقباد در قونیه جامع علاءالدین کیقباد در استان نیغده ترکیه

جامع علاءالدین کیقباد در استان نیغده ترکیه

هنر دوره سلجوقی، پارچ تزئین نقره، موزه بریتانیا

هنر دوره سلجوقی، پارچ تزئین نقره، موزه بریتانیا هنر دوره سلجوقی، موزه بروکلین

هنر دوره سلجوقی، موزه بروکلین

جستارهای وابسته

- طغرل بیک

- نبرد ملازگرد

- دقاق غز

- آل ارتق

- حشاشین

- اتابک

- دانشمندیان

- غزنویان

- سلجوق

- معماری سلجوقیان

- سلجوقیان

- سلجوقیان روم

- مهاجرت مردمان ترک

منابع

- Savory, R. M. and Roger Savory, Introduction to Islamic civilisation, (Cambridge University Press, 1976), 82.

- Black, Edwin, Banking on Baghdad: inside Iraq's 7,000-year history of war, profit and conflict, (John Wiley and sons, 2004), 38.

- C.E. Bosworth, "Turkish Expansion towards the west" in UNESCO HISTORY OF HUMANITY, Volume IV, titled "From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century", UNESCO Publishing / Routledge, p. 391: "While the Arabic language retained its primacy in such spheres as law, theology and science, the culture of the Seljuk court and secular literature within the sultanate became largely Persianized; this is seen in the early adoption of Persian epic names by the Seljuk rulers (Qubād, Kay Khusraw and so on) and in the use of Persian as a literary language (Turkish must have been essentially a vehicle for everyday speech at this time)

- Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world, Ed. Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie, (Elsevier Ltd. , 2009), 1110;Oghuz Turkic is first represented by Old Anatolian Turkish which was a subordinate written medium until the end of the Seljuk rule.".

- A New General Biographical Dictionary, Vol.2, Ed. Hugh James Rose, (London, 1853), 214.

- Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (New Brunswick:Rutgers University Press, 1988), 167.

- Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (New Brunswick:Rutgers University Press, 1988),159,161; "In 1194, Togrul III would succumb to the onslaught of the Khwarizmian Turks, who were destined at last to succeed the Seljuks to the empire of the Middle East."

- Rāvandī, Muḥammad (1385). Rāḥat al-ṣudūr va āyat al-surūr dar tārīkh-i āl-i saljūq. Tihrān: Intishārāt-i Asāṭīr. ISBN 9643313662.

- "Seljuq | History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- "Oğuz | people". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- «ČAḠRĪ BEG DĀWŪD – Encyclopaedia Iranica». www.iranicaonline.org. دریافتشده در ۲۰۲۰-۰۵-۳۰.

-

- "Aḥmad of Niǧde's al-Walad al-Shafīq and the Seljuk Past", A. C. S. Peacock, Anatolian Studies, Vol. 54, (2004), 97; "With the growth of Seljuk power in Rum, a more highly developed Muslim cultural life, based on the Persianate culture of the Great Seljuk court, was able to take root in Anatolia."

- Meisami, Julie Scott, Persian Historiography to the End of the Twelfth Century, (Edinburgh University Press, 1999), 143; "Nizam al-Mulk also attempted to organise the Saljuq administration according to the Persianate Ghaznavid model  k..."

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, "Šahrbānu", Online Edition: "here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkmen heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- Josef W. Meri, Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, 2005, p. 399

- Michael Mandelbaum, Central Asia and the World, Council on Foreign Relations (May 1994), p. 79

- Jonathan Dewald, Europe 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World, Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, p. 24: "Turcoman armies coming from the East had driven the Byzantines out of much of Asia Minor and established the Persianized sultanate of the Seljuks."

- Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (Rutgers University Press, 1991), 161, 164; "renewed the Seljuk attempt to found a great Turko-Persian empire in eastern Iran." "It is to be noted that the Seljuks, those Turkomans who became sultans of Persia, did not Turkify Persia-no doubt because they did not wish to do so. On the contrary, it was they who voluntarily became Persians and who, in the manner of the great old Sassanid kings, strove to protect the Iranian populations from the plundering of Ghuzz bands and save Iranian culture from the Turkoman menace."

- Wendy M. K. Shaw, Possessors and possessed: museums, archaeology, and the visualization of history in the late Ottoman Empire. University of California Press, 2003, شابک ۰−۵۲۰−۲۳۳۳۵−۲ , شابک ۹۷۸−۰−۵۲۰−۲۳۳۳۵−۵ ; p. 5.

-

- Jackson, P. (2002). "Review: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens". Journal of Islamic Studies. Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. 13 (1): 75–76. doi:10.1093/jis/13.1.75.

- Bosworth, C. E. (2001). 0Notes on Some Turkish Names in Abu 'l-Fadl Bayhaqi's Tarikh-i Mas'udi". Oriens, Vol. 36, 2001 (2001), pp. 299–313.

- Dani, A. H. , Masson, V. M. (Eds), Asimova, M. S. (Eds), Litvinsky, B. A. (Eds), Boaworth, C. E. (Eds). (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (Pvt. Ltd).

- Hancock, I. (2006). On Romani origins and identity. The Romani Archives and Documentation Center. The University of Texas at Austin.

- Asimov, M. S. , Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). (1998). History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV: "The Age of Achievement: AD 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century", Part One: "The Historical, Social and Economic Setting". Multiple History Series. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Dani, A. H. , Masson, V. M. (Eds), Asimova, M. S. (Eds), Litvinsky, B. A. (Eds), Boaworth, C. E. (Eds). (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (Pvt. Ltd).

- "Battle of Manzikert | Summary". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- "Toghrïl Beg | Muslim ruler". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

-

- C.E. Bosworth, "Turkmen Expansion towards the west" in UNESCO History of Humanity, Volume IV, titled "From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century", UNESCO Publishing / Routledge, p. 391: "While the Arabic language retained its primacy in such spheres as law, theology and science, the culture of the Seljuk court and secular literature within the sultanate became largely Persianized; this is seen in the early adoption of Persian epic names by the Seljuk rulers (Qubād, Kay Khusraw and so on) and in the use of Persian as a literary language (Turkmen must have been essentially a vehicle for everyday speech at this time). The process of Persianization accelerated in the thirteenth century with the presence in Konya of two of the most distinguished refugees fleeing before the Mongols, Bahā' al-Dīn Walad and his son Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, whose Mathnawī, composed in Konya, constitutes one of the crowning glories of classical Persian literature."

- Mehmed Fuad Köprülü, "Early Mystics in Turkish Literature", Translated by Gary Leiser and Robert Dankoff, Routledge, 2006, p. 149: "If we wish to sketch, in broad outline, the civilization created by the Seljuks of Anatolia, we must recognize that the local—i.e. , non-Muslim, element was fairly insignificant compared to the Turkish and Arab-Persian elements, and that the Persian element was paramount. The Seljuk rulers, to be sure, who were in contact with not only Muslim Persian civilization, but also with the Arab civilizations in al-jazlra and Syria—indeed, with all Muslim peoples as far as India—also had connections with {various} Byzantine courts. Some of these rulers, like the great 'Ala' al-Dln Kai-Qubad I himself, who married Byzantine princesses and thus strengthened relations with their neighbors to the west, lived for many years in Byzantium and became very familiar with the customs and ceremonial at the Byzantine court. Still, this close contact with the ancient Greco-Roman and Christian traditions only resulted in their adoption of a policy of tolerance toward art, aesthetic life, painting, music, independent thought—in short, toward those things that were frowned upon by the narrow and piously ascetic views {of their subjects}. The contact of the common people with the Greeks and Armenians had basically the same result. [Before coming to Anatolia,] the Turkmens had been in contact with many nations and had long shown their ability to synthesize the artistic elements that thev had adopted from these nations. When they settled in Anatolia, they encountered peoples with whom they had not yet been in contact and immediately established relations with them as well. Ala al-Din Kai-Qubad I established ties with the Genoese and, especially, the Venetians at the ports of Sinop and Antalya, which belonged to him, and granted them commercial and legal concessions. Meanwhile, the Mongol invasion, which caused a great number of scholars and artisans to flee from Turkmenistan, Iran, and Khwarazm and settle within the Empire of the Seljuks of Anatolia, resulted in a reinforcing of Persian influence on the Anatolian Turks. Indeed, despite all claims to the contrary, there is no question that Persian influence was paramount among the Seljuks of Anatolia. This is clearly revealed by the fact that the sultans who ascended the throne after Ghiyath al-Din Kai-Khusraw I assumed titles taken from ancient Persian mythology, like Kai-Khusraw, Kai-Ka us, and Kai-Qubad; and that. Ala' al-Din Kai-Qubad I had some passages from the Shahname inscribed on the walls of Konya and Sivas. When we take into consideration domestic life in the Konya courts and the sincerity of the favor and attachment of the rulers to Persian poets and Persian literature, then this fact [i.e., the importance of Persian influence] is undeniable. With regard to the private lives of the rulers, their amusements, and palace ceremonial, the most definite influence was also that of Iran, mixed with the early Turkish traditions, and not that of Byzantium."

- Stephen P. Blake, Shahjahanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India, 1639–1739. Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 123: "For the Seljuks and Il-Khanids in Iran it was the rulers rather than the conquered who were "Persianized and Islamicized"

-

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, "Šahrbānu", Online Edition: "here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkmen heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- O. Özgündenli, "Persian Manuscripts in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Libraries بایگانیشده در ۲۰۱۲-۰۱-۲۲ توسط Wayback Machine", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition

- Encyclopædia Britannica, "Seljuq", Online Edition: "Because the Turkish Seljuqs had no Islamic tradition or strong literary heritage of their own, they adopted the cultural language of their Persian instructors in Islam. Literary Persian thus spread to the whole of Iran, and the Arabic language disappeared in that country except in works of religious scholarship ..."

- M. Ravandi, "The Seljuq court at Konya and the Persianisation of Anatolian Cities", in Mesogeios (Mediterranean Studies), vol. 25-6 (2005), pp. 157–69

- F. Daftary, "Sectarian and National Movements in Iran, Khorasan, and Trasoxania during Umayyad and Early Abbasid Times", in History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol 4, pt. 1; edited by M.S. Asimov and C.E. Bosworth; UNESCO Publishing, Institute of Ismaili Studies: "Not only did the inhabitants of Khurasan not succumb to the language of the nomadic invaders, but they imposed their own tongue on them. The region could even assimilate the Turkic Ghaznavids and Seljuks (eleventh and twelfth centuries), the Timurids (fourteenth–fifteenth centuries), and the Qajars (nineteenth–twentieth centuries) ..."

- "The Turko-Persian tradition features Persian culture patronized by Turkic rulers." See Daniel Pipes: "The Event of Our Era: Former Soviet Muslim Republics Change the Middle East" in Michael Mandelbaum, "Central Asia and the World: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkemenistan and the World", Council on Foreign Relations, p. 79. Exact statement: "In Short, the Turko-Persian tradition featured Persian culture patronized by Turcophone rulers."

- Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (Rutgers University Press, 1991), 574.

- Bingham, Woodbridge, Hilary Conroy and Frank William Iklé, History of Asia, Vol.1, (Allyn and Bacon, 1964), 98.

- "Seljuq | History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

-

- An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples (Peter B. Golden. Otto Harrasowitz, 1992). pg 386: "Turkic penetration probably began in the Hunnic era and its aftermath. Steady pressure from Turkic nomads was typical of the Khazar era, although there are no unambiguous references to permanent settlements. These most certainly occurred with the arrival of the Oguz in the 11th century. The Turkicization of much of Azarbayjan, according to Soviet scholars, was completed largely during the Ilxanid period if not by late Seljuk times. Sumer, placing a slightly different emphasis on the data (more correct in my view), posts three periods which Turkicization took place: Seljuk, Mongol and Post-Mongol (Qara Qoyunlu, Aq Qoyunlu and Safavid). In the first two, Oguz Turkic tribes advanced or were driven to the western frontiers (Anatolia) and Northern Azarbaijan (Arran, the Mugan steppe). In the last period, the Turkic elements in Iran (derived from Oguz, with lesser admixture of Uygur, Qipchaq, Qaluq and other Turks brought to Iran during the Chinggisid era, as well as Turkicized Mongols) were joined now by Anatolian Turks migrating back to Iran. This marked the final stage of Turkicization. Although there is some evidence for the presence of Qipchaqs among the Turkic tribes coming to this region, there is little doubt that the critical mass which brought about this linguistic shift was provided by the same Oguz-Turkmen tribes that had come to Anatolia. The Azeris of today are an overwhelmingly sedentary, detribalized people. Anthropologically, they are little distinguished from the Iranian neighbors."

- John Perry: "We should distinguish two complementary ways in which the advent of the Turks affected the language map of Iran. First, since the Turkish-speaking rulers of most Iranian polities from the Ghaznavids and Seljuks onward were already Iranized and patronized Persian literature in their domains, the expansion of Turk-ruled empires served to expand the territorial domain of written Persian into the conquered areas, notably Anatolia and Central and South Asia. Secondly, the influx of massive Turkish-speaking populations (culminating with the rank and file of the Mongol armies) and their settlement in large areas of Iran (particularly in Azerbaijan and the northwest), progressively turkicized local speakers of Persian, Kurdish and other Iranian languages"

- According to C.E. Bosworth:

- According to Fridrik Thordarson:

- Andre Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Vol.2, 16. – via Questia (نیازمند آبونمان)

- Ed(s). "al- Niẓāmiyya , al- Madrasa." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2010, retrieved 20(03/2010)

- B.G. Massialas & S.A. Jarrar (1987), "Conflicts in education in the Arab world: The present challenge", Arab Studies Quarterly: "Subjects such as history, mathematics, physical sciences, and music were added to the curriculum of Al-Nizamiyah at a later time."

- دبیرینژاد، بدیعالله، سلاجقه و گسترش ادب ترکی. در: «چشمانداز ارتباطات فرهنگی»، تیر و مرداد ۱۳۸۴ - شماره ۱۷. صص۵۷–۶۰.

- دبیرینژاد، بدیعالله. صص۵۷–۶۰.

- فصلنامۀ تاریخ روابط خارجی.

- Wikipedia contributors, "Seljuq Empire," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seljuq_Empire&oldid=590795064 (accessed January 23, 2014).

- http://global.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/533602/Seljuq