ترکهای آناتولی

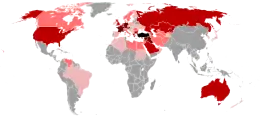

تُرکهای آناتولی (به ترکی استانبولی: Türkiye Türkleri یا Türkler) (در اصطلاح قدیمی فارسی: رومی، عثمانی) شاخهای از مردمان ترک هستند که در کشور خاورمیانه نظیر ترکیه، عراق، سوریه، کشورهای بالکان نظیر بلغارستان، قبرس، جمهوری ترک قبرس شمالی، در کشورهای اروپایی نظیر آلمان، بریتانیا زندگی میکنند و بیشترشان از اهل سنت هستند. این قوم حدود ۷۵ درصد از جمعیت ترکیه را تشکیل میدهند.

| جعبه اطلاعات این نوشتار، نیازمند ترجمه است. خواهشمند است این کار را با توجه به متن اصلی و رعایت سیاست ویرایش، دستور خط فارسی و برابر سازی به زبان فارسی انجام دهید. سپس این الگو را از بالای صفحه بردارید. |

Türkler | |

|---|---|

| |

| کل جمعیت | |

ح. 75 million

| |

| مناطق با جمعیت چشمگیر | |

| 56–60 million (2016 est.)[1] | |

| 315,000d[›][2][3] | |

| Diaspora in the West | |

| 2,774,000 (incl. citizens)[4] | |

| 1,000,000 (2012 est.)[5] | |

| 500,000a[›][6][7][8] | |

| 396,414e[›]–500,000c[›][9][10][11][12] | |

| 350,000–500,000[13][14] | |

| 200,000[15][16][17] | |

| 196,222–500,000 b[›][18][19][20][21] | |

| 70,440 e[›][22] | |

| 66,919–150,000 b[›][23][24][25][26] | |

| 49,948[27] | |

| 28,892 f[›]b[›][28] | |

| 63,955 b[›][29] | |

| 22,580 e[›][30] | |

| 3,000,000[31][32] | |

| 250,000-1,000,000[33][34] | |

| 150,000–200,000 b[›][35][36] | |

| 60,000[35] | |

| 50,000–200,000[37][38][39][40] | |

| 50,000 b[›][35] | |

| 22,000[41] | |

| 588,318–800,000[42][43][44] | |

| 77,959[45][46][47][48] | |

| 49,000 (official est.)–130,000 g[›][49][50][51][52] | |

| 27,700[53][54][55] | |

| 18,738[56] | |

| 109,883–150,000[57][58] | |

| 104,792–150,000 h[›][59][60] | |

| 40,953–50,000 h[›][61][60][62] | |

| 38,000–110,000 h[›][63][60][64][65] | |

| 15,000–20,000[66][60][67] | |

| 8,844[68] 10,000 Meskhetian Turks (academic estimates)[69][70][66] plus 5,394 Turkish nationals (2009)[71] | |

| زبانها | |

| Turkish | |

| دین | |

| Predominantly Islam[72][73][74][75] (Sunni • Alevi • Bektashi • Twelver Shia) Minority irreligious[72][76] • Christianity[77][78] • Judaism[79] | |

| قومیتهای وابسته | |

| Oghuz Turks | |

به مردم ترکزبان آسیای کوچک و آناتولی پیشتر در قلمرو ایران، «رومی»، «عثمانیها» یا «ترکان عثمانی» اطلاق میشد، و پس از فروپاشی حکومت عثمانی این اصطلاح کنار گذاشته شد. سرزمین مادریِ ترکهای عثمانی مکانی در آسیای مرکزی نزدیک آلتای است.

سلجوقیان مردمی ترکتبار از طوایف آسیای مرکزی بودند. به سال ۱۰۳۷ میلادی وارد ایران بزرگ شدند و نخستین حکومت اسلامی خود را بنا نهادند. سلجوقیان بهتدریج قسمتهایی از شرق و مرکز امپراتوری بیزانس روم را به تصرف خود درآوردند، و مسلمانان قسمتهایی از امپراتوری روم را تسخیر کردند و قونیه را بهعنوان مرکز انتخاب کردند.

ایلخانان و بیگلربیگیها: بیگلربیگی آناتولی گروهی کوچک از ترکها بودند که توسط بیگلر فرماندهی میشدند.

حکومت سلطان رومیِ سلجوق بعد از حملهٔ مغولان به پایان خود رسید. بعد از حملهٔ مغولها و تصرف آن، آناتولی به بخشهای مختلف بیگلربیگی تقسیم شد.

پدیدار شدن ترکها در آناتولی

آناتولی از دوران قدیم، خانه مردمان گوناگونی بود که از آن جمله آشوریان، هیتیها، لوویها، هوریها، ارمنیها، یونانیها، کیمریها، سکاها، گرجیها، کولخیسیها، کاریاییها، لیدیاییها، لیقیهایها، فریگیهایها، عربها، کردوها، کاپادوکیهایها و کیلیکیه ایها و بسیاری دیگر بودند.

حضور یونانیها در طول بسیاری از سواحل باعث شد تا بسیاری از این مردم تحت تأثیر یونان زبان خود را از دست داده و هلنی شوند. مخصوصاً در شهرها و در سواحل غربی و جنوبی رومیان تأثیر زیادی گذاشتند. با اینحال کماکان در شمال و شرق و علیالخصوص در روستاها بسیاری از گویشوران زبانهای بومی مانند ارمنیان و آشوریان زندگی میکردند.[80] اما در زمانی که ترکان برای نخستین بار در قرن یازدهم میلادی در این مناطق ظاهر شدند، فرهنگ یونانی تأثیر زیادی نداشت."[81] بیزانسیها به ویژه در مرزهایشان کسانی را که به فرقه مسیحی (غیر ارتودوکس) گرایش داشتند آزار میدادند و این موجب شده بود که گرایش به فرهنگ یونانی در آن مناطق کمتر شود.[81] بیزانسیها پیوسته گروههای بزرگی از مردم را برای یکسان سازی مذهبی و زبان یونانی مهاجرت میدادند. آنها همچنین کوشش میکردند تا تعداد زیادی از ارمنیها را آسیمیله کنند در نتیجه در قرن یازدهم میلادی، اشراف ارمنی از سرزمینهای خود کوچ و به غرب آناتولی مهاجرت کردند. نتیجه غیرقابل پیشبینی این رفتار، از دست رفتن فرماندهی نظامی محلی در مرزهای شرقی بود که راه را برای مهاجمان ترک باز کرد.[82] در اوایل قرن یازدهم جنگ با ترکها، موجب کشته شدن بسیاری از مردمان بومی شد و بسیاری از مردم هم به غلامی و بردگی گرفته شدند.[83] با خالی شدن این نواحی از سکنه، قبایل ترک به این نواحی کوچ کردند.[84]

با توجه به اینکه ترکان مناطق طبیعی متفاوتی را در یک سرزمین تصاحب کرده بودند،[85] تغییری در شیوه زندگیشان ایجاد شد و تعداد کمتری به گله داری و کوچ نشینی پرداختند. با اینحال اسباب ترک شدن این منطقه کمتر بخاطر ازدواج ترکان با مردم بومی بود و این تغییر بیشتر به علت تغییر مذهب بسیاری از مسیحیان و غیر مسیحیان به اسلام و تغییر زبانشان به زبان ترکی ایجاد شد. علت این تُرکیدگی مردمان بومی نخست ضعف فرهنگ یونانی در اغلب جمعیت بود و اینکه مردم سرزمینهای اشغال شده ترجیح میدادند تا به این شیوه مایملک و داراییهای خود را حفظ کنند.[86] یکی از نشانههای تُرکیدگی در دههٔ ۱۳۳۰ میلادی رخ داد. در آن زمان نامهای یونانی آناتولی را به نامهای ترکی تغییر دادند.[87]

اندرو مانگو میگوید:[88]

- «ملت ترک در طول قرونی که سلجوقیان و عثمانیان قدرت داشتند، شکل گرفت. قبایل ترک مهاجم، مردمان بومی را جایگزین نکردند بلکه با آنها وصلت کردند. در این میان مردمان هلنی آناتولی (یونانیان)، ارمنیها، مردم قفقاز، کردها، آشوریها و در بالکان اسلاوها، آلبانیاییها و دیگران بودند. پس از اینکه این مردم مسلمان و ترک شدند، از طریق سرزمینهای شمال دریای سیاه و قفقاز با دانشمند عرب یا هنرمند ایرانی با ماجراجوی اروپایی پیوند خوردند و در نتیجه ترکهای امروزی، گروههای قومی متعددی را در خود نمایش میدهند. برخی از آنها شرقی هستند، برخی دیگر خصوصیات بومی آناتولی دارند؛ برخی از ایشان بازماندگان اسلاوها، آلبانیها یا چرکسها هستند. برخی دیگر پوست تیره دارند، بسیاری مدیترانهای هستند، برخی از آسیای مرکزی و بسیاری هم شبیه ایرانیان اند. تعدادی که از لحاظ شماره اندک اند اما از جهت بازرگانی و دانشی مهم هستند، بازماندگان یهودیان اند که از دین یهود به اسلام تغییر مذهب دادند. اما همگی ترک هستند.»

ژنتیک

میزان سهم شارش ژنی از کوچنشینان ترکی آسیای مرکزی در خزانهٔ ژنی کنونی مردم ترک ترکیه، و نقش سکنی گزیدن مردم ترکی در آناتولی در قرن ۱۱ میلادی سوژهٔ مطالعات گوناگونی بودهاست. مطالعات متعدد نتیجه گرفتهاند که گروههای پیش از ترکیسازی و اسلامیسازی منبع اصلی ژنتیکی ترکهای امروزی ترکیه (یعنی مردم ترک آناتولی) هستند.[89]k[›][90][91][92][93]

اضافه بر این، مطالعات بسیاری اشاره میکنند که گرچه مهاجمان اولیه ترکی تهاجم را با عنصر مهم فرهنگی، از جمله وارد کردن زبان قدیمی ترکی آناتولی (نیای ترکی مدرن) و دین اسلام صورت دادند، مداخلهٔ ژنتیک آسیای مرکزی ممکن است خیلی کم بوده باشد.k[›][90][94] بنا بر American Journal of Physical Anthropology (2008), مردم ترک امروزی با جمعیتهای بالکان بیشتر در رابطهاند تا با جمعیتهای آسیای مرکزی،[95][96] و مطالعهای در خصوص بسامدهای آللی اشاره کرده که بین مغولها و ترکها، با وجود رابطه تاریخی زبانهایشان (ترکها و آلمانیها رابطهشان با جمعیتهای مغول به یک فاصله بود)، رابطهٔ ژنتیکی وجود ندارد.[97] چندین مطالعه یک مدل جایگزینی زبانی نخبگان با هدف تسلط فرهنگی را برای توضیح اختیار کردن زبان ترکی استانبولی به وسیلهٔ آناتولیاییهای باستان پیشنهاد کردند.[89]k[›][93]

.png.webp)

منابع

- CIA. "The World Factbook". Archived from the original on 2 July 2017.

- CIA. "The World Factbook". Archived from the original on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "KKTC 2011 NÜFUS VE KONUT SAYIMI" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- "Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund - Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus - Fachserie 1 Reihe 2.2 - 2017" (PDF). Statistisches Bundesamt (به آلمانی). p. 61. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Fransa Diyanet İşleri Türk İslam Birliği. "2011 YILI DİTİB KADIN KOLLARI GENEL TOPLANTISI PARİS DİTİB'DE YAPILDI". Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- Home Affairs Committee 2011, 38

- "UK immigration analysis needed on Turkish legal migration, say MPs". The Guardian. 1 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Federation of Turkish Associations UK (19 June 2008). "Short history of the Federation of Turkish Associations in UK". Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- "CBS Statline". opendata.cbs.nl.

- Netherlands Info Services. "Dutch Queen Tells Turkey 'First Steps Taken' On EU Membership Road". Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- Dutch News (6 March 2007). "Dutch Turks swindled, AFM to investigate". Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi 2008, 11.

- "Turkey's ambassador to Austria prompts immigration spat". BBC News. 10 November 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- CBN. "Turkey's Islamic Ambitions Grip Austria". Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- "Population par nationalité, sexe, groupe et classe d'âges au 1er janvier 2010 - - Home". Archived from the original on 22 December 2011.

- King Baudouin Foundation 2008, 5.

- De Morgen. "Koning Boudewijnstichting doorprikt clichés rond Belgische Turken". Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- U.S. Census Bureau. "TOTAL ANCESTRY REPORTED Universe: Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. "Immigration and Ethnicity: Turks". Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- The Washington Diplomat. "Census Takes Aim to Tally'Hard to Count' Populations". Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Farkas 2003, 40.

- Ständige ausländische Wohnbevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit, am Ende des Jahres بایگانیشده در ۳۰ ژانویه ۲۰۱۲ توسط Wayback Machine Swiss Federal Statistical Office, accessed 6 October 2014

- "Australian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "Old foes, new friends". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 April 2005. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- Presidency of the Republic of Turkey (2010). "Turkey-Australia: "From Çanakkale to a Great Friendship". Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- OECD (2009). "International Questionnaire: Migrant Education Policies in Response to Longstanding Diversity: TURKEY" (PDF). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. p. 3.

- Population of Sweden 31 December 2018 born in Turkey, which includes Turks, Assyrians, Kurds and others. [http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101E/FodelselandArK/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=daf5d50d-a31c-4045-8bfb-b4801e1c3cf9}}

- Statistikbanken. "Danmarks Statistik". Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". statcan.gc.ca.

- "I cittadini non comunitari regolarmente soggiornanti Ascolta". 5 August 2014. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Triana, María (2017), Managing Diversity in Organizations: A Global Perspective, Taylor & Francis, p. 168, ISBN 978-1-317-42368-3,

Turkmen, Iraqi citizens of Turkish origin, are the third largest ethnic group in Iraq after Arabs and Kurds and they are said to number about 3 million of Iraq's 34.7 million citizens according to the Iraqi Ministry of Planning.

- Bassem, Wassim (2016). "Iraq's Turkmens call for independent province". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016.

Turkmens are a mix of Sunnis and Shiites and are the third-largest ethnicity in Iraq after Arabs and Kurds, numbering about 3 million out of the total population of about 34.7 million, according to 2013 data from the Iraqi Ministry of Planning.

- Maisel, Sebastian (2016), Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building among a Double Minority, Lexington Books, p. 15, ISBN 978-0-7391-7775-4

- Pierre, Beckouche (2017), "The Country Reports: Syria", Europe's Mediterranean Neighbourhood, Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 178–180, ISBN 978-1-78643-149-3,

Before 2011, Syria's population was 74% Sunni Muslim, including...Turkmen (4%)...

- Akar 1993, 95.

- Karpat 2004, 12.

- Al-Akhbar. "Lebanese Turks Seek Political and Social Recognition". Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "Tension adds to existing wounds in Lebanon". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- Ahmed, Yusra (2015), Syrian Turkmen refugees face double suffering in Lebanon, Zaman Al Wasl, retrieved 11 October 2016

- Syrian Observer (2015). "Syria's Turkmen Refugees Face Cruel Reality in Lebanon". Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Council of Europe 2007, 131.

- National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (2011). "2011 Population Census in the Republic of Bulgaria (Final data)" (PDF). National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria.

- Sosyal 2011, 369.

- Bokova 2010, 170.

- "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2002" (PDF). Stat.gov.mk. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Republic of Macedonia State Statistical Office 2005, 34.

- Knowlton 2005, 66.

- Abrahams 1996, 53.

- "GREEK HELSINKI MONITOR". Minelres.lv. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Demographics of Greece". European Union National Languages. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- "Destroying Ethnic Identity: The Turks of Greece" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "Turks Of Western Thrace". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- (in Romanian) "Comunicat de presă privind rezultatele definitive ale Recensământului Populaţiei şi Locuinţelor – 2011", at the 2011 Romanian census site; accessed 11 July 2013

- Phinnemore 2006, 157.

- Constantin, Goschin & Dragusin 2008, 59.

- 2011 census in the Republic of Kosovo

- 2010 Russia census

- Ryazantsev 2009, 172.

- "Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике. Этнодемографический сборник Республики Казахстан 2014". Stat.gov.kz. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 13.

- Kyrgyz 2009 census

- IRIN Asia (9 June 2005). "KYRGYZSTAN: Focus on Mesketian Turks". Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- "Population by ethnic groups". 30 November 2012. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- UNHCR 1999, 14.

- NATO Parliamentary Assembly. "Minorities in the South Caucasus: Factor of Instability?". Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Council of Europe 2006, 23.

- Blacklock 2005, 8

- State Statistics Service of Ukraine. "Ukrainian Census (2001):The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue". Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Pentikäinen & Trier 2004, 20.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 14.

- Çalışma ve Sosyal Güvenlik Bakanlığı. "YURTDIŞINDAKİ VATANDAŞLARIMIZLA İLGİLİ SAYISAL BİLGİLER (31.12.2009 tarihi itibarıyla)". Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Religion, Secularism and the Veil in Daily Life Survey" (PDF). Konda Arastirma. September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- "IHGD - Soru Cevap - Azınlıklar". Sorular.rightsagenda.org. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "THE ALEVI OF ANATOLIA: TURKEY'S LARGEST MINORITY". Angelfire.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Shi'a". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "ReportDGResearchSocialValuesEN2.PDF" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "TURKEY - Christians in eastern Turkey worried despite church opening". Hurriyetdailynews.com. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "BBC News - When Muslims become Christians". News.bbc.co.uk. 21 April 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Mitchell, Stephen. 1993. Anatolia: land, men and gods in Asia Minor. Vol. 1, The Celts, and the impact of Roman rule. Clarendon Press. pp.172–176.

- (Langer and Blake 1932: 481)

- Charanis, Peter. 1961. "The Transfer of Population as a Policy in the Byzantine Empire." Comparative Studies in Society and History 3:140–154.

- (Vryonis 1971: 172)

- (Vryonis 1971: 184–194)

- (Langer and Blake 1932: 479-480)

- (Langer and Blake 1932: 481-483)

- (Langer and Blake 1932: 485)

- (Mango 2004:17–18)

- Yardumian, Aram; Schurr, Theodore G. (2011). "Who Are the Anatolian Turks?". Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia. 50: 6–42. doi:10.2753/AAE1061-1959500101. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

These data further solidify our case for a paternal G/J substratum in Anatolian populations, and for continuity between the Paleolithic/Neolithic and the current populations of Anatolia.

- Rosser, Z.; Zerjal, T.; Hurles, M.; Adojaan, M.; Alavantic, D.; Amorim, A.; Amos, W.; Armenteros, M.; Arroyo, E.; Barbujani, G.; Beckman, G.; Beckman, L.; Bertranpetit, J.; Bosch, E.; Bradley, D. G.; Brede, G.; Cooper, G.; Côrte-Real, H. B.; De Knijff, P.; Decorte, R.; Dubrova, Y. E.; Evgrafov, O.; Gilissen, A.; Glisic, S.; Gölge, M.; Hill, E. W.; Jeziorowska, A.; Kalaydjieva, L.; Kayser, M.; Kivisild, T. (2000). "Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Europe is Clinal and Influenced Primarily by Geography, Rather than by Language". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (6): 1526–1543. doi:10.1086/316890. PMC 1287948. PMID 11078479.

- Cinnioglu, C.; King, R.; Kivisild, T.; Kalfoğlu, E.; Atasoy, S.; Cavalleri, G. L.; Lillie, A. S.; Roseman, C. C.; Lin, A. A.; Prince, K.; Oefner, P. J.; Shen, P.; Semino, O.; Cavalli-Sforza, L. L.; Underhill, P. A. (2004). "Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia". Human Genetics. 114 (2): 127–148. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4. PMID 14586639.

- Arnaiz-Villena, A.; Karin, M.; Bendikuze, N.; Gomez-Casado, E.; Moscoso, J.; Silvera, C.; Oguz, F. S.; Sarper Diler, A.; De Pacho, A.; Allende, L.; Guillen, J.; Martinez Laso, J. (2001). "HLA alleles and haplotypes in the Turkish population: Relatedness to Kurds, Armenians and other Mediterraneans". Tissue Antigens. 57 (4): 308–317. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057004308.x. PMID 11380939.

- Wells, R. S.; Yuldasheva, N.; Ruzibakiev, R.; Underhill, P. A.; Evseeva, I.; Blue-Smith, J.; Jin, L.; Su, B.; Pitchappan, R.; Shanmugalakshmi, S.; Balakrishnan, K.; Read, M.; Pearson, N. M.; Zerjal, T.; Webster, M. T.; Zholoshvili, I.; Jamarjashvili, E.; Gambarov, S.; Nikbin, B.; Dostiev, A.; Aknazarov, O.; Zalloua, P.; Tsoy, I.; Kitaev, M.; Mirrakhimov, M.; Chariev, A.; Bodmer, W. F. (2001). "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (18): 10244–10249. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. PMC 56946. PMID 11526236.

- Arnaiz-Villena, A.; Gomez-Casado, E.; Martinez-Laso, J. (2002). "Population genetic relationships between Mediterranean populations determined by HLA allele distribution and a historic perspective". Tissue Antigens. 60 (2): 111–121. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600201.x. PMID 12392505.

- Berkman, C. C.; Dinc, H.; Sekeryapan, C.; Togan, I. (2008). "Alu insertion polymorphisms and an assessment of the genetic contribution of Central Asia to Anatolia with respect to the Balkans". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 136 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20772. PMID 18161848.

- Comas, D.; Schmid, H.; Braeuer, S.; Flaiz, C.; Busquets, A.; Calafell, F.; Bertranpetit, J.; Scheil, H. -G.; Huckenbeck, W.; Efremovska, L.; Schmidt, H. (2004). "Alu insertion polymorphisms in the Balkans and the origins of the Aromuns". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 120–127. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00080.x. PMID 15008791.

- Machulla, H. K. G.; Batnasan, D.; Steinborn, F.; Uyar, F. A.; Saruhan-Direskeneli, G.; Oguz, F. S.; Carin, M. N.; Dorak, M. T. (2003). "Genetic affinities among Mongol ethnic groups and their relationship to Turks". Tissue Antigens. 61 (4): 292–299. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00043.x. PMID 12753667.

الگو:شجرهنامه خاندان عثمانی