زبان اردو

زبان اُردو (اردو: اُردُو یا لشکری) یک زبان هندوآریایی است که بیشتر در جنوب آسیا گفتگو میشود.[9][10] اردو زبان ملی و میانجی رسمی پاکستان است.[11] اردو در هند یک زبان برنامه هشتم است که وضعیت، کارکرد و میراث فرهنگی آن توسط قانون اساسی هند به رسمیت شناخته شدهاست.[12][13] این زبان دارای وضعیت رسمی در چندین ایالت هند نیز هست.[11]

| اردو | |

|---|---|

| لشکری | |

| اُردُو | |

| |

| زبان بومی در | هند و پاکستان |

| منطقه | جنوب آسیا |

شمار گویشوران | زبان مادری: ۶۸٫۶۲ میلیون (۲۰۱۹) زبان دوم: ۱۰۱٫۵۸ میلیون (۲۰۱۹)[1] |

گونههای نخستین | |

| گویشها | |

| |

| وضعیت رسمی | |

زبان رسمی در | (ملی)

|

زبان اقلیت شناختهشده در | |

| تنظیمشده توسط | اداره ارتقای زبان ملی (پاکستان) شورای ملی ارتقای زبان اردو (هند) |

| کدهای زبان | |

| ایزو ۱–۶۳۹ | ur |

| ایزو ۲–۶۳۹ | urd |

| ایزو ۳–۶۳۹ | urd |

| گلاتولوگ | urdu1245[8] |

| زبانشناسی | 59-AAF-q |

زبان بیشینه

زبان اقلیت | |

اردو به عنوان گونه معیار فارسیشده زبان هندوستانی توصیف شدهاست.[14][15] اردو و هندی دارای پایه واژگان مشترک هندوآریایی و همانندیهای واجی و نحوی بسیار هستند که این باعث میشود که آنها در گفتار محاورهای برای یکدیگر قابل درک باشند.[16][17] اردوی رسمی واژگان ادبی و فنی و برخی ساختارهای دستوری ساده را از فارسی میگیرد،[18] در حالی که هندی رسمی اینها را از سانسکریت میگیرد.[18] زبان اردو بیش از نیمی از واژگان (بهطور مستقیم یا غیرمستقیم) و بخش عمده دستور زبان و الفبا و شعر خود را از زبان پارسی گرفتهاست. امروزه زبانهای فارسی و اردو از جمله نزدیکترین زبانهای جهان به یکدیگر بهشمار میروند. زبان اردو چون در محیط زبان فارسی بالیده و رشد کردهاست، به شدت تحت تأثیر این زبان قرار گرفتهاست. این تأثیر به ویژه در ادبیات اردو تا آن حد است که شعر اردو را پرتویی از شعر فارسی شمردهاند. ادبیات اردو در زیر بال شعر فارسی پرورش یافته، از این مادرخوانده نظم و نثر، سبک و مضمون، بحر و وزن و قافیه و شکل را به ارث برده و مخصوصاً الفاظش بهطور کامل از فارسی نشات گرفتهاست.[19]

اردو در سده هجدهم به زبان ادبی تبدیل شد و دو گونه معیار مشابه از آن در دهلی و لکهنو پدید آمد. از سال ۱۹۴۷ گونه معیار سوم آن نیز در کراچی پدید آمدهاست.[20][21] دکنی، گونه کهنتری که در گذشته در جنوب استفاده میشد، هماکنون منسوخ شدهاست.[21]

در سال ۱۸۳۷ هنگامی که کمپانی هند شرقی اردو را به جای فارسی، زبان دربار امپراتوریهای اسلامی هند انتخاب کرد، این زبان به عنوان زبان اداری کمپانی در سراسر شمال هند انتخاب شد.[22] عوامل مذهبی، اجتماعی و سیاسی که در دوره استعمار به وجود آمدند منجر به تمایز میان اردو و هندی و ستیز اردو و هندی شدند.[23]

طبق برآورد ناسیونال انسکلوپدین در سال ۲۰۱۰، اردو بیست و یکمین زبان نخست پرگویشور در جهان بود که ۶۶ میلیون نفر آن را به عنوان زبان مادری خود صحبت میکردند.[24] طبق تخمینهای اتنولوگ در سال ۲۰۱۸، اردو یازدهمین زبان پرگویشور جهان با ۱۷۰ میلیون گویشور کل، شامل کسانی که به آن به عنوان زبان دوم صحبت میکنند، بود.[25]

پیشینه

اردو همانند هندی گونهای از هندوستانی است.[26][27][28] برخی از زبانشناسان اظهار داشتند که نخستین شکلهای زبان اردو از گونه قرون وسطیایی اپبرمشه زبان شورسینی، یک زبان هندوآریایی میانه که نیای دیگر زبانهای نوین هندوآریایی است، تکامل یافتهاست.[29][30]

در منطقه دهلی هندوستان زبان مورد استفاده کهریبولی بود که کهنترین گونه آن به هندی باستان معروف است.[31] این زبان به گروه هندی غربی زبانهای هندوآریایی مرکزی تعلق داشت.[32][33] ارتباط فرهنگ هندوان و مسلمان در دوره حکومت مسلمانان در هند منجر به توسعه هندوستانی به عنوان فرآورده یک تهذیب ترکیبی گنگ-جامونی شد.[34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41] در شهرهایی مانند دهلی، هندی باستان شروع به گرفتن وامواژه از فارسی کرد و همچنان «هندی» و سپس نیز «هندوستانی» خوانده شد.[42][43][44][45][46]در جنوب هند (به ویژه در گلکنده و بیجاپور)، گونهای از این زبان در قرون وسطی شکوفا شد که به نام دکنی معروف است و از تلوگو و مراتی وامواژه پذیرفتهاست.[47][48][49]یک سنت ادبی آغازین هندوی توسط امیر خسرو در اواخر سده سیزدهم پایهگذاری شد.[50][51][52][53]از سده سیزدهم تا اواخر سده هجدهم به زبانی که اکنون اردو شناخته میشود هندی،[54] هندوی، هندوستانی،[55] دهلوی،[56] لاهوری ،[57] و لشکری[58] گفته میشد. در پایان سلطنت اورنگزیب در اوایل سده ۱۸، زبان مشترک دهلی شروع به نامیده شدن به عنوان زبان اردو کرد که از واژه ترکی اردو (ارتش) آمده بود و به معنی "زبان اردوگاه" یا به خود اردو " لشکری زبان "، بود.[59] در آغاز سلطاننشین دهلی، فارسی را به عنوان زبان رسمی خود در هند برگزید و این سیاست را امپراتوری گورکانی نیز ادامه داد که از سده ۱۶ تا ۱۸ در بیشتر مناطق شمالی جنوب آسیا حکومت و نفوذ فارسی را در هندوستان تقویت میکرد.[60][61]نام اردو نخستین بار در حدود سال ۱۷۸۰ میلادی توسط غلام همدانی مصحفی، شاعر اردوزبان، معرفی شد.[62][63] اردو به عنوان یک زبان ادبی، در محیطهای ممتاز و نخبه شکل گرفت.[64][65]در حالی که اردو دستور زبان و واژگان اصلی هندوآریایی گویش محلی کهریبولی را حفظ کرده بود، سامانه نوشتاری نستعلیق را،[66][67]که به عنوان سبک خوشنویسی فارسی توسعه یافته بود، برای نوشتن برگزید.[68]

اردو، که بیشتر توسط حاکمان انگلیسی هند به عنوان هندوستانی خوانده میشد،[69] با سیاستهای انگلیس برای سد نفوذ فارسی، در هند استعماری ترویج شد.[70]در هند استعماری، "مسلمانان و هندوها در استانهای متحد در قرن نوزدهم به یک زبان یکسان، یعنی هندوستانی، گفتگو میکردند؛ خواه آن را هندوستانی مینامیدند، خواه هندی، اردو، یا یکی از گویشهای محلی آن مانند برج یا اودهی. "[71] نخبگان جوامع مذهبی مسلمان و هندو در دادگاهها و ادارات دولتی این زبان را به خط فارسی-عربی مینوشتند؛ گرچه هندوها همچنان از خط دیواناگری در برخی موارد ادبی و مذهبی استفاده میکردند ولی همواره مسلمانان از خط فارسی-عربی استفاده میکردند.[72][73][74]اردو در سال ۱۸۳۷ به همراه انگلیسی جایگزین فارسی به عنوان زبان رسمی هند شد.[75]در مدارس اسلامی هند استعماری، مسلمانان فارسی و عربی را به عنوان زبان تمدن هندیاسلامی آموزش میدیدند. انگلیسیها برای ترویج سواد در میان مسلمانان هند و جذب آنها در مدارس دولتی، شروع به آموزش اردو با خط فارسی-عربی در این موسسات آموزشی کردند و از این پس، اردو توسط مسلمانان هند به عنوان نماد هویت دینی آنها دیده شد.[76]هندوها در شمال غربی هند، تحت عنوان آریا سماج، بر ضد استفاده تنها از خط فارسی-عربی دست به شورش زدند و اظهار داشتند که این زبان باید به خط دیواناگری نوشته شود،[77] که این نوشتن به دیواناگری باعث واکنش انجمن اسلامی لاهور شد.[78] هندی نوشتهشده به دیواناگری و اردوی به خط فارسی-عربی پایهگذار یک شکاف فرقهای به صورت «اردو» برای مسلمانان و «هندی» برای هندوها شد، شکافی که با چندپارگی هند استعماری به عنوان زبان کشور هند و زبان کشور پاکستان پس از استقلال رسمیت یافت (گرچه هنوز هم شاعران هندویی هستند که به نوشتن به اردو ادامه میدهند، از جمله گوپی چند نارنگ و گلزار).[79][80]

اردو در سال ۱۹۴۷ به عنوان زبان رسمی پاکستان انتخاب شد چرا که پیشتر زبان میانجی مسلمانان در شمال و شمال غربی هند بریتانیا بود؛[81] گرچه به عنوان زبان ادبی نویسندگان هند استعماری از جمله بمبئی، بنگال، اودیسا و تامیل نادو نیز به کار میرفت.[82] در سال ۱۹۷۳، اردو به عنوان تنها زبان ملی پاکستان شناخته شد - اگرچه به زبانهای انگلیسی و منطقهای نیز رسمیت رسمی داده شد.[83] پس از حمله شوروی به افغانستان در سال ۱۹۷۹ و ورود میلیونها پناهجوی افغانستانی به پاکستان، بسیاری از آنها، از جمله کسانی که به افغانستان بازگشتند،[84] به هندی-اردو تسلط دارند. این اتفاق با قرارگیری افغانستانیها در برابر رسانههای هند و فیلمها و آهنگهای عمدتاً هندی-اردوی بالیوود بیش از پیش تقویت شد.[85][86][87]

تلاشهایی برای پاکسازی اردو از واژگان پراکریت و سانسکریت و هندی از واژههای فارسی صورت گرفتهاست؛ واژگان جدید برای اردو عمدتاً از فارسی و عربی و برای هندی از سانسکریت گزیده میشوند.[88][89]انگلیسی به عنوان زبان رسمی، تأثیر زیادی روی هر دو اعمال کردهاست.[90]جنبشی به سوی فارسیسازی بیش از حد اردو از زمان استقلال آن در پاکستان در سال ۱۹۴۷ پدیدار شد که به اندازه سانسکریتسازی بیش از حد هندی «مصنوعی» است.[91]فارسیسازی بیش از حد اردو تا حدی به دلیل افزایش سانسکریتسازی هندی انجام شد.[92]با این حال، سبکی از اردو که بهطور روزمره در پاکستان گفتگو میشود، شبیه هندوستانی خنثی است که به عنوان زبان میانجی در شمال شبهقاره هند عمل میکند.[93][94]

پراکندگی جغرافیایی

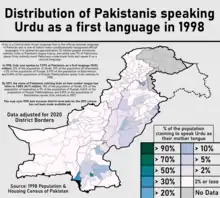

بیش از ۱۰۰ میلیون گویشور بومی اردو در هند و پاکستان با هم وجود دارد: طبق سرشماری سال ۲۰۱۱، ۵۰٫۸ میلیون اردوزبان در هند (۴٫۳۴٪ از کل جمعیت) وجود داشت[95][96] و در برآوردی در سال ۲۰۰۶ تقریباً ۱۶ میلیون اردوزبان در پاکستان یافت میشد.[97] در انگلستان، عربستان سعودی، ایالات متحده و بنگلادش نیز چند صد هزار گویشور اردو وجود دارند.[98]با این حال، هندوستانی، که اردو یکی از گونههای آن است، بسیار گستردهتر صحبت میشود و سومین زبان رایج در جهان پس از ماندارین و انگلیسی است.[99]نحو (دستور زبان)، صرف و واژگان اصلی اردو و هندی اساساً یکسان هستند - بنابراین زبان شناسان معمولاً آنها را به عنوان یک زبان واحد میشمارند، در حالی که برخی ادعا میکنند که آنها به دلایل سیاسی اجتماعی باید به عنوان دو زبان متفاوت در نظر گرفته شوند.[100]

اردو به دلیل تعامل با زبانهای دیگر، در هر کجا که صحبت شود بومیسازی شدهاست؛ از جمله در پاکستان. اردو در پاکستان دستخوش تغییراتی شدهاست و واژههای زیادی را از زبانهای منطقهای وام گرفتهاست، بنابراین این به اردوزبانان در پاکستان این امکان را میدهد که خودشان را راحتتر بشناسند و به آن زبان طعم و مزه پاکستانی میبخشد. به همین ترتیب، گویشهایی اردویی را که در هند صحبت میشود، همانند اردوی معیار لکهنو و دهلی و همچنین دکنی جنوب هند (دکن)، نیز میتوان به راحتی شناخت.[20][101]اگر یک گویشور اردو و هندی از استفاده از واژگان ادبی خودداری کنند، به دلیل شباهت این دو، به راحتی میتوانند سخن یکدیگر را درک کنند.[16]

پاکستان

گرچه بیشتر جمعیت پاکستان به اردو تسلط دارند، تنها ۷ درصد از آنها از آن به عنوان زبان مادری خود را در سرشماری ۱۹۹۲ یاد کردند.[102]بیشتر حدود سه میلیون پناهجوی افغانستانی با خاستگاههای مختلف قومی (مانند پشتون، تاجیک، ازبک، هزاره و ترکمن) که بیش از بیست و پنج سال در پاکستان اقامت داشتند، نیز به زبان اردو تسلط دارند.[103]مهاجران از سال ۱۹۴۷ بیشینه جمعیت را در شهر کراچی تشکیل دادهاند.[104]روزنامههای زیادی به زبان اردو در پاکستان منتشر میشوند، از جمله روزنامههای دیلی جنگ ، نوای وقت و ملت.

هیچ منطقهای در پاکستان از اردو به عنوان زبان مادری خود استفاده نمیکند، اگرچه این زبان به عنوان زبان نخست مهاجران مسلمان (معروف به مهاجران) در پاکستان که پس از استقلال در سال ۱۹۴۷ هند را ترک کردند، صحبت میشود.[105]اردو در سال ۱۹۴۷ به عنوان نمادی از وحدت برای دولت جدید پاکستان انتخاب شد، زیرا پیشتر به عنوان زبان میانجی در میان مسلمانان در شمال و شمال غربی هند انگلیس عمل کرده بود.[106] این زبان در تمام استانها / سرزمینهای پاکستان نوشته و گفتگو میشود و مورد استفاده قرار میگیرد، هرچند مردم مناطق مختلف ممکن است زبانهای بومی مختلفی داشته باشند.

اردو به عنوان یک درس اجباری تا دبیرستان در هر دو سامانه دبیرستانهای انگلیسی و اردو تدریس میشود، که میلیونها اردوزبانان زبان دوم را در میان افرادی که زبان مادری آنها از دیگر زبانهای پاکستان است، تولید کردهاست- که این به نوبه خود منجر به به جذب واژگان از زبانهای مختلف منطقهای پاکستانی و همچنین جذب واژگان اردو به زبانهای منطقهای شدهاست.[107] با وجود اینکه مردمان بسیاری به اردو سخن میگویند، این زبان عطر و طعم خاصی از پاکستان پیدا کردهاست که باعث تمایز بیشتر آن از زبان اردویی که توسط گویشوران بومی آن صحبت میشود، و در نتیجه گوناگونی بیشتری در زبان، شدهاست.[108]

هند

در هند، اردو در مناطقی که اقلیتهای بزرگی از مسلمان وجود دارند یا شهرهایی که در گذشته پایگاه امپراتوریهای مسلمان بودهاند، گفتگو میشود. این شامل بخشهایی از اوتار پرادش، مادها پرادش، بیهار، تلانگانا، آندرا پرادش، ماهاراشترا، کارناتاکا و شهرستانهایی مانند لکهنو، دهلی، مالیرکوتله، بریلی، میروت، سهارانپور، مظفرنگر، رورکی، دیوبند، مرادآباد، اعظمگره، بیجنور، نجیبآباد، رامپور، علیگر، اللهآباد، گوراخوپور، آگره، کانپور، بدایون، بوپال، حیدرآباد، اورنگآباد، بنگلور، کلکته، میسور، پتنه، گلبرگه، پاربانی، ناندید، کوچی، مالهگاون، بیدر، آجمبر و احمدآباد میشود. برخی از مدارس هند زبان اردو را به عنوان زبان نخست آموزش میدهند و برنامههای درسی و امتحانات را به این زبان دارند. در صنعت بالیوود هند معمولاً از زبان اردو - به ویژه در آهنگها - استفاده میکند.[109]

هند دارای بیش از ۳٬۰۰۰ نشریه اردو از جمله ۴۰۵ روزنامه روزانه اردو است.[110][111]روزنامههایی مانند نشاط نیوز اردو، صحرای اردو، دیلی سالار، هندوستان اکسپرس، دیلی پاسبان، سیاست دیلی، منصف دیلی و انقلاب در بنگلور، ملگاون، میسور، حیدرآباد و بمبئی به اردو منتشر و توزیع میشوند.[112]

دیگر جایها

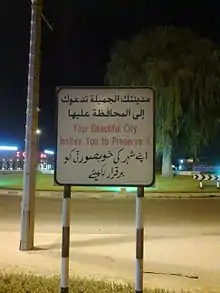

در بیرون از جنوب آسیا، اردو توسط بسیاری از کارگران مهاجر جنوب آسیایی در مراکز عمده شهری کشورهای حاشیه خلیج فارس صحبت میشود. این زبان همچنین توسط تعداد زیادی از مهاجران و فرزندان آنها در مراکز مهم شهری انگلستان، ایالات متحده، کانادا، آلمان، نروژ و استرالیا گفتگو میشود.[113] اردو در کنار عربی، دو زبان پرگویشور مهاجران در کاتالونیا هستند.[114]

رسمیت

از اردو یک گونه کمتر رسمی خود به عنوان ریخته، به معنی «مخلوط خشن» یاد شدهاست. گونه رسمیتر اردو گاهی اوقات به صورت زبان اردوی معلی با اشاره به ارتش شاهنشاهی[115] یا لشکری زبان[116] یا به سادگی فقط لشکری یاد میشود.[117] ریشهشناسی واژهای که در اردو استفاده میشود، در بیشتر موارد تعیین میکند که چقدر گفتار فرد مودبانه یا پالایهشدهاست. برای نمونه، اردو زبانان بین پانی و آب تمایز قائل میشوند که هر دو به معنای «آب» است؛ اولی در محاوره استفاده میشود و ریشه در سانسکریت دارد، اما دومی بهطور رسمی و شاعرانه استفاده میشود و اصالتاً فارسی است.

استفاده از واژگان فارسی یا عربی نشاندهنده سطح سخنرانی رسمیتر و بالاتر است. به همین ترتیب، اگر از ساختارهای دستور زبان فارسی یا عربی، مانند اضافات، در اردو استفاده شود، سطح گفتار رسمیتر و بالاتر را نشان میدهد. اگر واژهای از سانسکریت استفاده شود، سطح گفتار محاورهای و شخصی در نظر گرفته میشود.[118]

پاکستان

اردو تنها زبان ملی و یکی از دو زبان رسمی پاکستان (همراه با انگلیسی) است.[119]این زبان در سراسر کشور گفتگو میشود و قابل فهم است، در حالی که زبانهای هر ایالت (زبانهایی که در مناطق مختلف صحبت میشوند) زبانهای استانی نامیده میشوند. تنها ۷٫۵۷٪ پاکستانیها اردو را به عنوان زبان نخست خود صحبت میکنند.[120]وضعیت رسمی اردو به این معنی است که این زبان به عنوان زبان دوم یا سوم بهطور گسترده در سراسر پاکستان درک و صحبت میشود. از اردو به گستردگی در آموزش، ادبیات، اداره کشور و تجارت استفاده میشود،[121] اگرچه در عمل، انگلیسی به جای اردو در ردههای بالاتر دولتی استفاده میشود.[122] ماده (۱) ۲۵۱ قانون اساسی پاکستان دستور میدهد که اردو به عنوان تنها زبان دولت به کار گرفته شود، اگرچه انگلیسی همچنان پرکاربردترین زبان در سطوح بالاتر دولت پاکستان است.[123]

هند

اردو یکی از زبانهای به رسمیت شناختهشده هند و یکی از پنج زبان رسمی جامو و کشمیر، یکی از دو زبان رسمی تلانگانا و همچنین "زبان رسمی اضافی" در ایالتهای اوتار پرادش، بیهار، جارکند، بنگال غربی و پایتخت ملی، دهلی نو، است.[124][125]در ایالت جامو و کشمیر پیشین، در بخش ۱۴۵ قانون اساسی چنین آمدهاست: "زبان رسمی دولت باید اردو باشد اما اگر قانونگذار مقرر کند باید از انگلیسی نیز باید برای تمام اهداف رسمی ایالت استفاده شود. "[126]

هند یک دفتر دولتی را برای ارتقا زبان اردو در سال ۱۹۶۹ تأسیس کرد، اگرچه اداره مرکزی هندی در اوایل سال ۱۹۶۰ تأسیس شد و ترویج هندی با بودجه بهتر و به صورت پیشرفتهتری انجام میشود[127] در حالی که با ارتقا هندی وضعیت اردو تضعیف شدهاست.[128] سازمانهای خصوصی هندی مانند انجمن ترقی اردو، شورای دینی تعلیمی و اردو مشافیز دسته، استفاده از اردو را ترویج و آن را حفظ میکنند؛ انجمن با موفقیت یک کارزار را آغاز کرد که اردو را به عنوان زبان رسمی بیهار در دهه ۱۹۷۰ معرفی شود.[129]

واجشناسی

همخوانها

| لبی | دندانی | لثوی | برگشته | کامی | نرمکامی | زبانکی | چاکنایی | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| خیشومی | m م | n ن | ŋ ن٘ | ||||||

| انسدادی/ انسایشی |

بیواک | p پ | t ت | ʈ ٹ | tʃ چ | k ک | (q) ق | ||

| بیواک حلقی | pʰ په | tʰ ته | ʈʰ ٹه | tʃʰ چه | kʰ که | ||||

| واکدار | b ب | d د | ɖ ڈ | dʒ ج | ɡ گ | ||||

| واکدار حلقی | bʰ به | dʰ ده | ɖʰ ڈه | dʒʰ جه | gʰ گه | ||||

| زنشی/لرزشی | صاف | r ر | ɽ ڑ | ||||||

| واکدار حلقی | ɽʱ ڑه | ||||||||

| سایشی | بیواک | f ف | s س | ʃ ش | x خ | ɦ ه | |||

| واکدار | ʋ و | z ز | (ʒ) ژ | (ɣ) غ | |||||

| ناسوده | l ل | j ی | |||||||

واژگان

سید احمد دهلوی، یک فرهنگنویس از قرن ۱۹ که فرهنگ اشرفیه اردو را نوشتهاست، برآورد کردهاست که ۷۵ درصد از واژگان[133][134][135] و در حدود ۹۹٪ از فعلهای اردو ریشه در سانسکریت و پراکریت دارند.[136][137] حدود ۲۵٪[138][139][140][141] تا ۳۰٪[142]از واژگان اردو از فارسی و به میزان کمتری عربی از طریق فارسی،[143] وام گرفته شدهاند. افروز تاج، زبانشناس دانشگاه کارولینای شمالی در چپل هیل، در آماری نسبت وامواژگان فارسی به واژگان بومی سانسکریت در اردوی ادبی ۱ به ۳ برآورد کردهاست.[144] طبق برآوردی دیگر ۶۰٪ از واژگان زبان اردو از فارسی گرفته شدهاست.[145]

«گرایش به فارسیسازی» اردو از قرن هجدهم توسط مکتب شاعران اردو در دهلی آغاز شد، گرچه نویسندگان دیگری مانند معراجی به گونه سانسکریتشده این زبان مینوشتند.[147]از سال ۱۹۴۷ در پاکستان حرکت به سمت فارسیسازی بیش از حد اردو صورت گرفتهاست که توسط بسیاری از نویسندگان این کشور پذیرفته شدهاست.[148]به همین ترتیب، برخی از متون اردو میتوانند از ۷۰٪ واژه وام فارسی-عربی تشکیل شوند.[149] برخی از اردوزبانان پاکستانی به دلیل قرار گرفتن در معرض رسانههای هندی، واژگان هندی را در گفتار خود گنجاندهاند.[150][151]در هند، اردو به اندازه پاکستان از هندی جدا نشدهاست.[152]

بیشتر وامواژگان اردو اسم و صفت هستند.[153]بسیاری از واژگان عربی اردو از طریق فارسی وارد آن شدهاند،[154]و گاه تلفظ، کاربرد و معنای آنها متفاوت از عربی است. در اردو همچنین وامواژگان کمی از پرتغالی یافت میشوند. چند نمونه از این واژگان عبارتند از: از کابی ("chave": کلید)، گیرجا ("igreja": کلیسا)، کامرا ("cámara": اتاق)، قمیز ("camisa": پیراهن)، مز ("mesa": جدول).[155]

اگر چه نام اردو از واژه ترکی اردو (ارتش) یا اردا آمده که از آن واژه انگلیسی horde (گروه ترکان و مغولان) نیز مشتق شدهاست،[156]اردو دارای وامواژگان بسیار کمی از ترکی است[157]و از نظر ژنتیکی نیز به زبانهای ترکی ارتباطی ندارد. بیشتر واژگان اردو که از جغتایی و عربی ریشه گرفتهاند، در اصل از راه فارسی آمدهاند و از این رو نسخه فارسیشده واژگان اصلی هستند. به عنوان مثال، تاء مربوطه (ة) عربی در اردو همانند فارسی به ـه (ه) یا ت (ت) تغییر پیدا میکند.[158] اندک وامواژگان ترکی موجود در اردو از زبان جغتایی، یک زبان ترکی از آسیای میانه، آمدهاند. اردو و ترکی هر دو از عربی و فارسی وام بسیار گرفتهاند، از این رو بسیاری از واژههای آن دو در تلفظ شباهت دارند.[159]

در برخی متون تا ۷۰ درصد واژگان زبان اردو، فارسی است. سید احمد دهلوی میزان آن را حدود ۳۰ درصد میداند. همیرا شهباز استادیار یکی از دانشگاههای پاکستان اعتقاد دارد ۶۰ درصد کلمات زبان اردو فارسی است. زمانی بیش از هشتاد یا نود درصد کلمات تشکیل دهنده زبان اردو واژگان فارسی یا عربی بودهاست. ورود واژگان و عبارات انگلیسی و زبانهای بومی به زبان اردو این نسبتها را برهم زده و در فرهنگ لغت اردوی «فیروزاللغات» واژهها و ترکیبهای فارسی بیش از بیستوپنج درصد نیست. بررسی زبان اردو نشان میدهد که تأثیر زبان فارسی بر اردو اگرچه برای گسترش دامنهٔ ادبیات در این زبان بوده ولی این اثرپذیری دایرهٔ گستردهای داشته و شامل اسامی، افعال، حروف، محاورات، تشبیهات، استعارهها، ترکیبها و ضربالمثلها میشود. مشترکات فارسی و اردو بسیار زیاد است و زبان فارسی نه تنها بر اردو بلکه بر دیگر زبانهای پاکستان نیز اثرات عمیق بر جای گذاشتهاست. نخستین زبانی که در شبه قاره و پاکستان از فارسی بسیار متأثر گردید، زبان پنجابی بود. زبان پنجابی بدون واسطه با زبان فارسی ارتباط برقرار کرد و از آمیزش آنها چنان خمیرمایهای آماده کرد که چون به دهلی رسید زبان اردو به وجود آمد.[160][161] طبق تخمین دیگر ۶۰ درصد واژگان زبان اردو از فارسی گرفته شدهاست.[162]

اردو ایرانی شده- اسلامی سازی زبان هندوستانی است. اردو گویشی از این زبان است که در پاکستان به کار میرود، با خط فارسی نوشته میشود و مملو از واژگان تخصصی و ادبی فارسی و واژگان عربی (راه یافته از طریق زبان فارسی) است. اما هندی گویشی است که در هندوستان به کار میرود و با خط دیواناگری نوشته میشود و در انتخاب واژگان تخصصی و ادبی بر زبان سانسکریت تکیه میکند. زبان واحد هندوستانی از لحاظ مجموع گویشوران چهارمین زبان جهان است. اردو زبان مادری کمتر از هشت درصد مردم پاکستان است، اما نزدیک به نود درصد مردم این کشور اردو را بلدند و میتوانند به این زبان صحبت کنند. لازم است ذکر شود که برخی از مردم افغانستان هم به این زبان صحبت میکنند.

هویت فرهنگی

هند استعماری

جو مذهبی و اجتماعی در اوایل قرن نوزدهم هند انگلیس نقش به سزایی در توسعه گونه اردو داشت. هندی در پی آن به گونه متمایزی تبدیل شد که توسط افرادی که در پی ایجاد هویت هندو در برابر استعمار بودند، صحبت میشد.[23]همانند هندی که برای ایجاد هویت متمایز هندو از هندوستانی جدا شد، اردو نیز برای ایجاد هویت اسلامی برای جمعیت مسلمان هند بریتانیا به کار گرفته شد.[163]استفاده از اردو فقط به شمال هند محدود نمیشد و این زبان به عنوان زبان ادبی نویسندگان هندی در مناطق بمبئی، بنگال، اودیسا و تامیل نادو نیز مورد استفاده قرار میگرفت.[164]

از آنجا که اردو و هندی به ترتیب به نماد مذهبی و اجتماعی برای مسلمانان و هندوان تبدیل شدند، هر گونه خط ویژه خود را برگزید. طبق سنت اسلامی، عربی، زبان پیامبر و وحی قرآن، دارای اهمیت و قدرت معنوی است.[165] از آنجا که اردو به عنوان وسیلهای برای وحدت مسلمانان در شمال هند و بعداً پاکستان در نظر گرفته شده بود، یک خط فارسی-عربی اصلاحشده را برای نوشتار برگزید.[166][167]

پاکستان

اردو همچنان که جمهوری اسلامی پاکستان با هدف ایجاد میهن برای مسلمانان جنوب آسیا تأسیس شد، به نقش خود در توسعه هویت مسلمان ادامه داد. با وجود داشتن چندین زبان و گویش متمایز در مناطق پاکستان، نیاز فوری به بهکارگیری یک زبان واحد حس میشد. اردو در سال ۱۹۴۷ به عنوان نمادی از وحدت برای دولت جدید پاکستان انتخاب شد، زیرا پیشتر به عنوان زبان میانجی در میان مسلمانان در شمال و شمال غربی هند انگلیس کار میکرد.[168] اردو همچنین به عنوان گنجینه میراث فرهنگی و اجتماعی پاکستان دیده میشود.[169]

در حالی که اردو و اسلام با هم نقش مهمی در رشد هویت ملی پاکستان داشتند، اختلافات در دهه ۱۹۵۰ (به ویژه اختلافات در پاکستان شرقی، که بنگالی زبان غالب بود)، ایده اردو به عنوان یک نماد ملی و کاربردی بودن آن به عنوان زبان میانجی را به چالش کشید. هنگامی که در پاکستان شرقی سابق (بنگلادش کنونی) انگلیسی و بنگالی نیز به عنوان زبان رسمی پذیرفته شدند، از اختلافات موجود در مورد اردو کاسته شد.[170]

سامانه نوشتاری

اردو از راست به چپ به گونهای اصلاحشده از الفبای فارسی نوشته میشود که خود گونهٔ اصلاحشده الفبای عربی است. اردو با سبک نستعلیق خوشنویسی فارسی ارتباط دارد، در حالی که عربی بهطور کلی به سبک نسخ یا رقعه نوشته میشود. حروفچینی نستعلیق دشوار است، بنابراین تا اواخر دهه ۱۹۸۰ روزنامههای اردو به صورت دستنویس توسط استادان خوشنویسی، که به نام خوشنویس شناخته میشدند، نوشته میشد. یک روزنامه دستنویس اردو به نام د مسلمان هنوز هم هر روز در چنای منتشر میشود.[171]

یک گونه کاملاً فارسیشده و فنی از زبان اردو زبان میانجی دادگاههای حقوقی دولت انگلیس در بنگال و استانهای شمال غربی و اودیسا بود. تا اواخر قرن نوزدهم، کلیه روند دادرسی در این گونه اردو رسماً به خط فارسی نوشته میشد. در سال ۱۸۸۰، سر اشلی ادن، ستوان فرماندار بنگال در هند استعماری، استفاده از الفبای فارسی را در دادگاههای حقوقی بنگال لغو کرد و دستور داد که از کیتهی استفاده شود که خطی بود که اردو و هندی را با آن مینوشتند. در استان بیهار نیز زبان دادگاه اردو بود که با خط کیتهی نوشته میشد.[172][173][174][175]ارتباط کیتهی با اردو و هندی در نهایت با رقابت سیاسی میان این زبانها و خطهای آنها که اردو در پیوند با خط فارسی بود، از میان رفت.[176]

اخیراً در هند، اردوزبانان از دیواناگری برای انتشار مجلات ادبی اردو استفاده میکنند و روشهای جدیدی و متمایزی را برای علامتگذاری اردو در دیواناگری ابداع کردهاند. این ناشران به منظور بازنمایی ریشهشناسی فارسی-عربی واژههای اردو، ویژگیهای جدید نگارشی را به دیواناگری وارد کردهاند. یک مثال استفاده از अ (دیواناگری الف) با علائم واکهای برای نشان دادن ع است که بر خلاف قوانین املانویسی هندی است. به استفاده از دیواناگری به ناشران اردو مخاطبان بیشتری میدهد، در حالی که تغییرات مربوط به املانویسی به آنها کمک میکند تا هویت متمایز اردو را حفظ کنند.[177]

گویشها

اردو دارای چند گویش به رسمیت شناخته شده، از جمله دکنی، داکایی، ریخته و اردوی بومی نوین (بر اساس گویش کهریبولی منطقه دهلی) است. دکنی در منطقه دکن در جنوب هند صحبت میشود. این گویش با داشتن واژگان مراتی و کونکانی و همچنین برخی از واژگان از عربی، فارسی و جغتایی که در گویش معیار اردو یافت نمیشود، متمایز است. دکنی بهطور گسترده در تمام مناطق ماهاراشترا، تلانگانا، آندرا پرادش و کارناتاکا صحبت میشود. اردو در سایر مناطق هند نیز خوانده و نوشته میشود. شماری روزنامههای روزانه و چندین مجله ماهانه به زبان اردو نیز در این ایالتها منتشر میشوند.

اردوی داکایی گویش بومی شهر باستانی داکا (دهاکه) در بنگلادش است که قدمت آن به دوران مغول بازمیگردد. با این حال، پس از جنبش زبان بنگالی در قرن بیستم، محبوبیت آن، حتی در میان گویشوران بومیش، به تدریج کاهش یافتهاست. این زبان توسط دولت بنگلادش به رسمیت شناخته نشدهاست. اردوی صحبت شده توسط پاکستانیهای ساکن در بنگلادش با این گویش متفاوت است.

کدگزینی

بسیاری از اردوزبانان دوزبانه یا چندزبانه هستند. برخی از آنها که به دو زبان اردو و انگلیسی آشنایی دارند، گاه میان اردو و انگلیسی کدگزینی میکنند که به آن «اردیش» گفته میشود. دولت پاکستان در ۱۴ اوت ۲۰۱۵ جنبش علم را با یک برنامه درسی هماهنگ در اردیش راهاندازی کرد. احسن اقبال، وزیر فدرال پاکستان، گفت: «اکنون دولت در حال کار بر روی یک برنامه درسی جدید برای ارائه یک واسطه جدید به دانشجویان است که ترکیبی از دو زبان اردو و انگلیسی باشد و نام آن را اردیش بگذارد.»[178][179][180]

شعر اردو

شعر اردو که به شدت از ادبیات فارسی تأثیر گرفته یکی از گونههای غنی ادبیات در پاکستان و شمال هند است. بخش عمدهای از بزرگان این زبان از شیعیان و مرثیه سرایان عاشورا بودهاند. در مقایسه با شعر فارسی، قدمت شعر اردو زیاد نیست. با اینکه شعر اردو همه داروندار اولیهاش از شعر فارسی مستعار بوده است، با گذرِ زمان فاصلههای قابلِ ملاحظهای بین شعر اردو و فارسی ایجاد شده است و امروز بسیاری از نکاتی که در شعرِ اردو موردِ قبول واقع شدهاند، به صورت اعمال در شعرِ فارسی اشکال محسوب میگردند و برعکس. مانند غزلهای فارسی سبک هندی، غزل اردو هم غزل بیتمحور است و هر بیتش به تنهایی معنای جداگانهای را به مخاطب ارائه میدهد و قابلیت این را دارد که به طور مجزا در هر کجا استفاده شود. هرچند شعر کلاسیک فارسی هم همینطور بوده است. اما امروز در ایران بیشتر غزلها منسجم بوده و انسجام عمودی دارند. حتی غزلهایی که موضوعاتِ مختلفی در آنها گنجانیده شدهاند و در نگاه اول غزل بیتمحور به نظر میآیند، یک انسجام کلی موضوعی در خود دارند. [182]

مقایسه با هندی

از نظر زبانشناسی، هندی و اردو دو گونهٔ معیار از یک زبان و نسبت به یکدیگر قابل فهم هستند.[183] هندی به خط دیواناگری نوشته میشود و دارای واژگان سانسکریت بیشتری نسبت به اردو است، درحالی که اردو به خط عربی نوشته میشود و دارای وامواژههای فارسی و عربی بیشتری نسبت به هندی است. گرچه هر دو دارای یک هسته واژهای از کلمات بومی پراکریت و سانسکریت با شمار زیادی وامواژهٔ فارسی و عربی هستند.[184][185] به همین دلیل و همچنین این واقعیت که این دو گونه از یک دستور زبان یکسان برخوردار هستند،[186][16][184] همه زبانشناسان آنها را دو گونهٔ معیار از یک زبان به نام هندوستانی یا هندی-اردو میدانند.[183][186][16][187]

هندی رایجترین زبان رسمی در هند و اردو زبان ملی و میانجی پاکستان و یکی از ۲۲ زبان رسمی هند و زبان رسمی در اوتار پرادش، جامو و کشمیر و دهلی است. در نظر گرفتن هندی و اردو به عنوان زبانهای جداگانه عمدتاً ناشی از سیاست و به دلیل رقابت هند و پاکستان است.[188]

گویشوران اردو بر پایه کشور

جدول زیر تعداد اردوزبانان در برخی کشورها را نشان میدهد.

| کشور | جمعیت | گویشران بومی | گویشوران زبان دوم |

|---|---|---|---|

| ۱٬۲۹۶٬۸۳۴٬۰۴۲[189] | ۵۰٬۷۷۲٬۶۳۱[81] | ۱۲٬۱۵۱٬۷۱۵[81] | |

| ۲۰۷٬۸۶۲٬۵۱۸[190] | ۱۵٬۱۰۰٬۰۰۰[191] | ۱۶۴٬۰۰۰٬۰۰۰[191] | |

| ۳۴٬۹۴۰٬۸۳۷[192] | – | ۱٬۰۴۸٬۲۲۵[192] | |

| ۳۳٬۰۹۱٬۱۱۳[193] | ۷۴۰٬۰۰۰[191] | – | |

| ۲۹٬۷۱۷٬۵۸۷[194] | ۶۹۱٬۵۴۶[195] | – | |

| ۶۵٬۱۰۵٬۲۴۶[196] | ۴۰۰٬۰۰۰[197] | – | |

| ۳۲۹٬۲۵۶٬۴۶۵[198] | ۳۹۷٬۵۰۲[199] | – | |

| ۱۵۹٬۴۵۳٬۰۰۱[200] | ۲۵۰٬۰۰۰[201] | – | |

| ۳۵٬۸۸۱٬۶۵۹[202] | ۲۴۳٬۰۹۰[203] | – | |

| ۲٬۳۶۳٬۵۶۹[204] | ۱۸۰٬۰۰۰[191] | – | |

| ۴٬۶۱۳٬۲۴۱[205] | ۷۳٬۰۰۰[191] | – | |

| ۸۳٬۰۲۴٬۷۴۵[206] | ۸۹٬۰۰۰[191] | – | |

| ۲۵٬۷۷۹٬۸۰۰[207] | ۶۹٬۰۰۰[191] | – | |

| ۱٬۴۴۲٬۶۵۹[208] | ۶۵٬۰۰۰[191] | – | |

| ۵٬۳۷۲٬۱۹۱[209] | ۳۸٬۰۰۰[191] | – | |

| ۸۱٬۲۵۷٬۲۳۹[210] | ۲۴٬۰۰۰[191] | – | |

| ۸۰٬۴۵۷٬۷۳۷[211] | ۲۳٬۰۰۰[191] | – |

جستارهای وابسته

- فارسی و اردو

- زبان و ادب فارسی در هند

- فرهنگ هندوپارسی

- ادب پارسی در هند

- زبان فارسی در کشمیر

- سرایندگان ایرانی در شبهقاره هند

- زبان فارسی در شبهقاره هندوستان

- پارسیان در امپراتوری گورکانی

- واجشناسی فارسی

- خط در ایران

- فارسی دری

- تأثیرات زبان فارسی بر زبان اردو

- تأثیرات زبان فارسی بر زبان عربی

- زبان فارسی در افغانستان

- زبان فارسی در ازبکستان

- زبان پنجابی

- زبان پشتو

- زبان فارسی

- ستیز اردو و هندی

منابع

- Urdu at اتنولوگ (22nd ed., 2019)

- Hindustani (2005). Keith Brown, ed. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- Gaurav Takkar. "Short Term Programmes". punarbhava.in. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Indo-Pakistani Sign Language", Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics

- "Urdu is Telangana's second official language". The Indian Express. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Urdu is second official language in Telangana as state passes Bill". The News Minute. 17 November 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 - Chapter 1: Founding Provisions". www.gov.za. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Urdu". Glottolog 2.2. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (5 December 2019), Urdu language, Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved October 17, 2020,

member of the Indo-Aryan group within the Indo-European family of languages. Urdu is spoken as a first language by nearly 70 million people and as a second language by more than 100 million people, predominantly in Pakistan and India. It is the official state language of Pakistan and is also officially recognized, or “scheduled,” in the constitution of India.

- Urdu (n), Oxford English Dictionary, June 2020, retrieved 11 September 2020,

An Indo-Aryan language of northern South Asia (now esp. Pakistan), closely related to Hindi but written in a modified form of the Arabic script and having many loanwords from Persian and Arabic.

- Muzaffar, Sharmin; Behera, Pitambar (2014). "Error analysis of the Urdu verb markers: a comparative study on Google and Bing machine translation platforms". Aligarh Journal of Linguistics. 4 (1–2): 1.

Modern Standard Urdu, a register of the Hindustani language, is the national language, lingua-franca and is one of the two official languages along with English in Pakistan and is spoken in all over the world. It is also one of the 22 scheduled languages and officially recognized languages in the Constitution of India and has been conferred status of the official language in many Indian states of Bihar, Telangana, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and New Delhi. Urdu is one of the members of the new or modern Indo-Aryan language group within the Indo-European family of languages.

- Gazzola, Michele; Wickström, Bengt-Arne (2016). The Economics of Language Policy. MIT Press. pp. 469–. ISBN 978-0-262-03470-8. Quote: "The Eighth Schedule recognizes India’s national languages as including the major regional languages as well as others, such as Sanskrit and Urdu, which contribute to India’s cultural heritage. … The original list of fourteen languages in the Eighth Schedule at the time of the adoption of the Constitution in 1949 has now grown to twenty-two."

- Groff, Cynthia (2017). The Ecology of Language in Multilingual India: Voices of Women and Educators in the Himalayan Foothills. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-1-137-51961-0. Quote: "As Mahapatra says: “It is generally believed that the significance for the Eighth Schedule lies in providing a list of languages from which Hindi is directed to draw the appropriate forms, style and expressions for its enrichment” … Being recognized in the Constitution, however, has had significant relevance for a language's status and functions.

- Gibson, Mary (13 May 2011). Indian Angles: English Verse in Colonial India from Jones to Tagore. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-4358-3.

Bayly's description of Hindustani (roughly Hindi/Urdu) is helpful here; he uses the term Urdu to represent "the more refined and Persianised form of the common north Indian language Hindustani" (Empire and Information, 193); Bayly more or less follows the late eighteenth-century scholar Sirajuddin Ali Arzu, who proposed a typology of language that ran from "pure Sanskrit, through popular and regional variations of Hindustani to Urdu, which incorporated many loan words from Persian and Arabic. His emphasis on the unity of languages reflected the view of the Sanskrit grammarians and also affirmed the linguistic unity of the north Indian ecumene. What emerged was a kind of register of language types which were appropriate to different conditions. ...But the abiding impression is of linguistic plurality running through the whole society and an easier adaptation to circumstances in both spoken and written speech" (193). The more Persianized the language, the more likely it was to be written in Arabic script; the more Sanskritized the language; the more likely it was to be written in Devanagari.

- Basu, Manisha (2017). The Rhetoric of Hindutva. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-14987-8.

Urdu, like Hindi, was a standardized register of the Hindustani language deriving from the Dehlavi dialect and emerged in the eighteenth century under the rule of the late Mughals.

- Gube, Jan; Gao, Fang (2019). Education, Ethnicity and Equity in the Multilingual Asian Context. انتشارات اسپرینگر. ISBN 978-981-13-3125-1.

The national language of India and Pakistan 'Standard Urdu' is mutually intelligible with 'Standard Hindi' because both languages share the same Indic base and are all but indistinguishable in phonology.

- Clyne, Michael (24 May 2012). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. p. 385. ISBN 978-3-11-088814-0.

With the consolidation of the different linguistic bases of Khari Boli there were three distinct varieties of Hindi-Urdu: the High Hindi with predominant Sanskrit vocabulary, the High-Urdu with predominant Perso-Arabic vocabulary and casual or colloquial Hindustani which was commonly spoken among both the Hindus and Muslims in the provinces of north India. The last phase of the emergence of Hindi and Urdu as pluricentric national varieties extends from the late 1920s till the partition of India in 1947.

- Kiss, Tibor; Alexiadou, Artemis (10 March 2015). Syntax - Theory and Analysis. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 1479. ISBN 978-3-11-036368-5.

- https://www.sid.ir/fa/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=106606

- Schmidt, Ruth Laila (8 December 2005). Urdu: An Essential Grammar. روتلج. ISBN 978-1-134-71319-6.

Historically, Urdu developed from the sub-regional language of the Delhi area, which became a literary language in the eighteenth century. Two quite similar standard forms of the language developed in Delhi, and in Lucknow in modern Uttar Pradesh. Since 1947, a third form, Karachi standard Urdu, has evolved.

- Mahapatra, B. P. (1989). Constitutional languages. دانشگاه لاوال. p. 553. ISBN 978-2-7637-7186-1.

Modern Urdu is a fairly homogenous language. An older southern form, Deccani Urdu, is now obsolete. Two varieties however, must be mentioned viz. the Urdu of Delhi, and the Urdu of Lucknow. Both are almost identical, differing only in some minor points. Both of these varieties are considered 'Standard Urdu' with some minor divergences.

- Metcalf, Barbara D. (2014). Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860-1900. Princeton University Press. pp. 207–. ISBN 978-1-4008-5610-7.

The basis of that shift was the decision made by the government in 1837 to replace Persian as court language by the various vernaculars of the country. Urdu was identified as the regional vernacular in Bihar, Oudh, the North-Western Provinces, and Punjab, and hence was made the language of government across upper India.

- Ahmad, Rizwan (1 July 2008). "Scripting a new identity: The battle for Devanagari in nineteenth century India". Journal of Pragmatics. 40 (7): 1163–1183. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2007.06.005.

- Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin. Asterisks mark the 2010 estimates بایگانیشده در ۱۱ نوامبر ۲۰۱۲ توسط Wayback Machine for the top dozen languages.

- "What are the top 200 most spoken languages?". Ethnologue. 3 October 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Dua, Hans R. (1992).

- Kachru, Yamuna (2008), Braj Kachru; Yamuna Kachru; S. N. Sridhar, eds., Hindi-Urdu-Hindustani, Language in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 82, ISBN 978-0-521-78653-9

- Qalamdaar, Azad (27 December 2010). "Hamari History". Hamari Boli Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010.

Historically, Hindustani developed in the post-12th century period under the impact of the incoming Afghans and Turks as a linguistic modus vivendi from the sub-regional apabhramshas of north-western India. Its first major folk poet was the great Persian master, Amir Khusrau (1253–1325), who is known to have composed dohas (couplets) and riddles in the newly-formed speech, then called 'Hindavi'. Through the medieval time, this mixed speech was variously called by various speech sub-groups as 'Hindavi', 'Zaban-e-Hind', 'Hindi', 'Zaban-e-Dehli', 'Rekhta', 'Gujarii. 'Dakkhani', 'Zaban-e-Urdu-e-Mualla', 'Zaban-e-Urdu', or just 'Urdu'. By the late 11th century, the name 'Hindustani' was in vogue and had become the lingua franca for most of northern India. A sub-dialect called Khari Boli was spoken in and around Delhi region at the start of 13th century when the Delhi Sultanate was established. Khari Boli gradually became the prestige dialect of Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu) and became the basis of modern Standard Hindi & Urdu.

- Schmidt, Ruth Laila. "1 Brief history and geography of Urdu 1.1 History and sociocultural position."

- Malik, Shahbaz, Shareef Kunjahi, Mir Tanha Yousafi, Sanawar Chadhar, Alam Lohar, Abid Tamimi, Anwar Masood et al.

- Mody, Sujata Sudhakar (2008). Literature, Language, and Nation Formation: The Story of a Modern Hindi Journal 1900-1920. University of California, Berkeley. p. 7.

...Hindustani, Rekhta, and Urdu as later names of the old Hindi (a.k.a. Hindavi).

- Taj, Afroz (1997). "About Hindi-Urdu". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- "Two Languages or One?". hindiurduflagship.org. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

Hindi and Urdu developed from the "khari boli" dialect spoken in the Delhi region of northern India.

- Farooqi, M. (2012). Urdu Literary Culture: Vernacular Modernity in the Writing of Muhammad Hasan Askari. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-02692-7.

Historically speaking, Urdu grew out of interaction between Hindus and Muslims. He noted that Urdu is not the language of Muslims alone, although Muslims may have played a larger role in making it a literary language. Hindu poets and writers could and did bring specifically Hindu cultural elements into Urdu and these were accepted.

- King, Christopher Rolland (1999). One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-19-565112-6.

Educated Muslims, for the most part supporters of Urdu, rejected the Hindu linguistic heritage and emphasized the joint Hindu-Muslim origins of Urdu.

- Taylor, Insup; Olson, David R. (1995). Scripts and Literacy: Reading and Learning to Read Alphabets, Syllabaries, and Characters. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-7923-2912-1.

Urdu emerged as the language of contact between Hindu inhabitants and Muslim invaders to India in the 11th century.

- Dhulipala, Venkat (2000). The Politics of Secularism: Medieval Indian Historiography and the Sufis. University of Wisconsin–Madison. p. 27.

Persian became the court language, and many Persian words crept into popular usage. The composite culture of northern India, known as the Ganga Jamuni tehzeeb was a product of the interaction between Hindu society and Islam.

- Indian Journal of Social Work, Volume 4. Tata Institute of Social Sciences. 1943. p. 264.

... more words of Sanskrit origin but 75% of the vocabulary is common. It is also admitted that while this language is known as Hindustani, … Muslims call it Urdu and the Hindus call it Hindi. … Urdu is a national language evolved through years of Hindu and Muslim cultural contact and, as stated by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, is essentially an Indian language and has no place outside.

- "Women of the Indian Sub-Continent: Makings of a Culture - Rekhta Foundation". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

The "Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb" is one such instance of the composite culture that marks various regions of the country. Prevalent in the North, particularly in the central plains, it is born of the union between the Hindu and Muslim cultures. Most of the temples were lined along the Ganges and the Khanqah (Sufi school of thought) were situated along the Yamuna river (also called Jamuna). Thus, it came to be known as the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, with the word "tehzeeb" meaning culture. More than communal harmony, its most beautiful by-product was "Hindustani" which later gave us the Hindi and Urdu languages.

- Zahur-ud-Din (1985). Development of Urdu Language and Literature in the Jammu Region. Gulshan Publishers. p. 13.

The beginning of the language, now known as Urdu, should therefore, be placed in this period of the earlier Hindu Muslim contact in the Sindh and Punjab areas that took place in early quarter of the 8th century A.D.

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

The primary sources of non-IA loans into MSH are Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, Turkic and English. Conversational registers of Hindi/Urdu (not to mentioned formal registers of Urdu) employ large numbers of Persian and Arabic loanwords, although in Sanskritised registers many of these words are replaced by tatsama forms from Sanskrit. The Persian and Arabic lexical elements in Hindi result from the effects of centuries of Islamic administrative rule over much of north India in the centuries before the establishment of British rule in India. Although it is conventional to differentiate among Persian and Arabic loan elements into Hindi/Urdu, in practice it is often difficult to separate these strands from one another. The Arabic (and also Turkic) lexemes borrowed into Hindi frequently were mediated through Persian, as a result of which a thorough intertwining of Persian and Arabic elements took place, as manifest by such phenomena as hybrid compounds and compound words. Moreover, although the dominant trajectory of lexical borrowing was from Arabic into Persian, and thence into Hindi/Urdu, examples can be found of words that in origin are actually Persian loanwords into both Arabic and Hindi/Urdu.

- Kesavan, B. S. (1997). History Of Printing And Publishing in India. National Book Trust, India. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-237-2120-0.

It might be useful to recall here that Old Hindi or Hindavi, which was a naturally Persian- mixed language in the largest measure, has played this role before, as we have seen, for five or six centuries.

- Bhat, M. Ashraf (2017). The Changing Language Roles and Linguistic Identities of the Kashmiri Speech Community. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4438-6260-8.

Although it has borrowed a large number of lexical items from Persian and some from Turkish, it is a derivative of Hindvi (also called 'early Urdu'), the parent of both modern Hindi and Urdu. It originated as a new, common language of Delhi, which has been called Hindavi or Dahlavi by Amir Khusrau. After the advent of the Mughals on the stage of Indian history, the Hindavi language enjoyed greater space and acceptance. Persian words and phrases came into vogue. The Hindavi of that period was known as Rekhta, or Hindustani, and only later as Urdu. Perfect amity and tolerance between Hindus and Muslims tended to foster Rekhta or Urdu, which represented the principle of unity in diversity, thus marking a feature of Indian life at its best. The ordinary spoken version ('bazaar Urdu') was almost identical to the popularly spoken version of Hindi. Most prominent scholars in India hold the view that Urdu is neither a Muslim nor a Hindu language; it is an outcome of a multicultural and multi-religious encounter.

- Strnad, Jaroslav (2013). Morphology and Syntax of Old Hindī: Edition and Analysis of One Hundred Kabīr vānī Poems from Rājasthān. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-25489-3.

Quite different group of nouns occurring with the ending -a in the dir. plural consists of words of Arabic or Persian origin borrowed by the Old Hindi with their Persian plural endings.

- Rahman, Tariq (2001). From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History (PDF). Oxford University Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-19-906313-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Taj, Afroz (1997). "About Hindi-Urdu". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Khan, Abdul Rashid (2001). The All India Muslim Educational Conference: Its Contribution to the Cultural Development of Indian Muslims, 1886-1947. Oxford University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-19-579375-8.

After the conquest of the Deccan, Urdu received the liberal patronage of the courts of Golconda and Bijapur. Consequently, Urdu borrowed words from the local language of Telugu and Marathi as well as from Sanskrit.

- Luniya, Bhanwarlal Nathuram (1978). Life and Culture in Medieval India. Kamal Prakashan. p. 311.

Under the liberal patronage of the courts of Golconda and Bijapur, Urdu borrowed words from the local languages like Telugu and Marathi as well as from Sanskrit, but its themes were moulded on Persian models.

- Kesavan, Bellary Shamanna (1985). History of Printing and Publishing in India: Origins of printing and publishing in the Hindi heartland. National Book Trust. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-237-2120-0.

The Mohammedans of the Deccan thus called their Hindustani tongue Dakhani (Dakhini), Gujari or Bhaka (Bhakha) which was a symbol of their belonging to Muslim conquering and ruling group in the Deccan and South India where overwhelming number of Hindus spoke Marathi, Kannada, Telugu and Tamil.

- "Amīr Khosrow - Indian poet".

- Jaswant Lal Mehta (1980). Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. 1. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 10. ISBN 9788120706170.

- Bakshi, Shiri Ram; Mittra, Sangh (2002). Hazart Nizam-Ud-Din Auliya and Hazrat Khwaja Muinuddin Chisti. Criterion. ISBN 9788179380222.

- "Urdu language". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Rahman, Tariq (2001). From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History (PDF). Oxford University Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-19-906313-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Bhat, M. Ashraf (2017). The Changing Language Roles and Linguistic Identities of the Kashmiri Speech Community. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4438-6260-8.

Although it has borrowed a large number of lexical items from Persian and some from Turkish, it is a derivative of Hindvi (also called 'early Urdu'), the parent of both modern Hindi and Urdu. It originated as a new, common language of Delhi, which has been called Hindavi or Dahlavi by Amir Khusrau. After the advent of the Mughals on the stage of Indian history, the Hindavi language enjoyed greater space and acceptance. Persian words and phrases came into vogue. The Hindavi of that period was known as Rekhta, or Hindustani, and only later as Urdu. Perfect amity and tolerance between Hindus and Muslims tended to foster Rekhta or Urdu, which represented the principle of unity in diversity, thus marking a feature of Indian life at its best. The ordinary spoken version ('bazaar Urdu') was almost identical to the popularly spoken version of Hindi. Most prominent scholars in India hold the view that Urdu is neither a Muslim nor a Hindu language; it is an outcome of a multicultural and multi-religious encounter.

- Rahman, Tariq (2001). From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History (PDF). Oxford University Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-19-906313-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Rauf Parekh (25 August 2014). "Literary Notes: Common misconceptions about Urdu". dawn.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

Urdu did not get its present name till late 18th Century and before that had had a number of different names – including Hindi, Hindvi, Hindustani, Dehlvi, Gujri, Dakkani, Lahori and even Moors – though it was born much earlier.

- Malik, Muhammad Kamran, and Syed Mansoor Sarwar.

- Alyssa Ayres (23 July 2009). Speaking Like a State: Language and Nationalism in Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-51931-1.

- First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913–1936. Brill Academic Publishers. 1993. p. 1024. ISBN 9789004097964.

Whilst the Muhammadan rulers of India spoke Persian, which enjoyed the prestige of being their court language, the common language of the country continued to be Hindi, derived through Prakrit from Sanskrit. On this dialect of the common people was grafted the Persian language, which brought a new language, Urdu, into existence. Sir George Grierson, in the Linguistic Survey of India, assigns no distinct place to Urdu, but treats it as an offshoot of Western Hindi.

- Strnad, Jaroslav (2013). Morphology and Syntax of Old Hindī: Edition and Analysis of One Hundred Kabīr vānī Poems from Rājasthān. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-25489-3.

Quite different group of nouns occurring with the ending -a in the dir. plural consists of words of Arabic or Persian origin borrowed by the Old Hindi with their Persian plural endings.

- Faruqi, Shamsur Rahman (2003), Sheldon Pollock, ed., A Long History of Urdu Literary Culture Part 1, Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions From South Asia, University of California Press, p. 806, ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4

- Rahman, Tariq (2001). From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History (PDF). Oxford University Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-19-906313-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Coatsworth, John (2015). Global Connections: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. United States: Cambridge Univ Pr. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-521-76106-2.

- Tariq Rahman (2011). "Urdu as the Language of Education in British India" (PDF). Pakistan Journal of History and Culture. NIHCR. 32 (2): 1–42.

- Taj, Afroz (1997). "About Hindi-Urdu". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Delacy, Richard; Ahmed, Shahara (2005). Hindi, Urdu & Bengali. Lonely Planet. pp. 11–12.

Hindi and Urdu are generally considered to be one spoken language with two different literary traditions. That means that Hindi and Urdu speakers who shop in the same markets (and watch the same Bollywood films) have no problems understanding each other -- they'd both say yeh kitne kaa hay for 'How much is it?' -- but the written form for Hindi will be यह कितने का है? and the Urdu one will be یه کتنی کا هی؟ Hindi is written from left to right in the Devanagari script, and is the official language of India, along with English. Urdu, on the other hand, is written from right to left in the Nastaliq script (a modified form of the Arabic script) and is the national language of Pakistan. It's also one of the official languages of the Indian states of Bihar and Jammu & Kashmir. Considered as one, these tongues constitute the second most spoken language in the world, sometimes called Hindustani. In their daily lives, Hindi and Urdu speakers communicate in their 'different' languages without major problems. … Both Hindi and Urdu developed from Classical Sanskrit, which appeared in the Indus Valley (modern Pakistan and northwest India) at about the start of the Common Era. The first old Hindi (or Apabhransha) poetry was written in the year 769 AD, and by the European Middle Ages it became known as 'Hindvi'. Muslim Turks invaded the Punjab in 1027 and took control of Delhi in 1193. They paved the way for the Islamic Mughal Empire, which ruled northern India from the 16th century until it was defeated by the British Raj in the mid-19th century. It was at this time that the language of this book began to take form, a mixture of Hindvi grammar with Arabic, Persian and Turkish vocabulary. The Muslim speakers of Hindvi began to write in the Arabic script, creating Urdu, while the Hindu population incorporated the new words but continued to write in Devanagari script.

- Holt, P. M.; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 723. ISBN 0-521-29138-0.

- Rehman, Tariq. "The Teaching of Urdu in British India".

- Rahman, Tariq (2000). "The Teaching of Urdu in British India" (PDF). The Annual of Urdu Studies. 15: 55. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2014.

- Hutchinson, John; Smith, Anthony D. (2000). Nationalism: Critical Concepts in Political Science. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-20112-4.

In the nineteenth century in north India, before the extension of the British system of government schools, Urdu was not used in its written form as a medium of instruction in traditional Islamic schools, where Muslim children were taught Persian and Arabic, the traditional languages of Islam and Muslim culture. It was only when the Muslim elites of north India and the British decided that Muslims were backward in education in relation to Hindus and should be encouraged to attend government schools that it was felt necessary to offer Urdu in the Persian-Arabic script as an inducement to Muslims to attend the schools. And it was only after the Hindi-Urdu controversy developed that Urdu, once disdained by Muslim elites in north India and not even taught in the Muslim religious schools in the early nineteenth century, became a symbol of Muslim identity second to Islam itself. A second point revealed by the Hindi-Urdu controversy in north India is how symbols may be used to separate peoples who, in fact, share aspects of culture. It is well known that ordinary Muslims and Hindus alike spoke the same language in the United Provinces in the nineteenth century, namely Hindustani, whether called by that name or whether called Hindi, Urdu, or one of the regional dialects such as Braj or Awadhi. Although a variety of styles of Hindi-Urdu were in use in the nineteenth century among different social classes and status groups, the legal and administrative elites in courts and government offices, Hindus and Muslims alike, used Urdu in the Persian-Arabic script.

- Hutchinson, John; Smith, Anthony D. (2000). Nationalism: Critical Concepts in Political Science. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-20112-4.

In the nineteenth century in north India, before the extension of the British system of government schools, Urdu was not used in its written form as a medium of instruction in traditional Islamic schools, where Muslim children were taught Persian and Arabic, the traditional languages of Islam and Muslim culture. It was only when the Muslim elites of north India and the British decided that Muslims were backward in education in relation to Hindus and should be encouraged to attend government schools that it was felt necessary to offer Urdu in the Persian-Arabic script as an inducement to Muslims to attend the schools. And it was only after the Hindi-Urdu controversy developed that Urdu, once disdained by Muslim elites in north India and not even taught in the Muslim religious schools in the early nineteenth century, became a symbol of Muslim identity second to Islam itself. A second point revealed by the Hindi-Urdu controversy in north India is how symbols may be used to separate peoples who, in fact, share aspects of culture. It is well known that ordinary Muslims and Hindus alike spoke the same language in the United Provinces in the nineteenth century, namely Hindustani, whether called by that name or whether called Hindi, Urdu, or one of the regional dialects such as Braj or Awadhi. Although a variety of styles of Hindi-Urdu were in use in the nineteenth century among different social classes and status groups, the legal and administrative elites in courts and government offices, Hindus and Muslims alike, used Urdu in the Persian-Arabic script.

- Delacy, Richard; Ahmed, Shahara (2005). Hindi, Urdu & Bengali. Lonely Planet. pp. 11–12.

Hindi and Urdu are generally considered to be one spoken language with two different literary traditions. That means that Hindi and Urdu speakers who shop in the same markets (and watch the same Bollywood films) have no problems understanding each other -- they'd both say yeh kitne kaa hay for 'How much is it?' -- but the written form for Hindi will be यह कितने का है? and the Urdu one will be یه کتنی کا هی؟ Hindi is written from left to right in the Devanagari script, and is the official language of India, along with English. Urdu, on the other hand, is written from right to left in the Nastaliq script (a modified form of the Arabic script) and is the national language of Pakistan. It's also one of the official languages of the Indian states of Bihar and Jammu & Kashmir. Considered as one, these tongues constitute the second most spoken language in the world, sometimes called Hindustani. In their daily lives, Hindi and Urdu speakers communicate in their 'different' languages without major problems. … Both Hindi and Urdu developed from Classical Sanskrit, which appeared in the Indus Valley (modern Pakistan and northwest India) at about the start of the Common Era. The first old Hindi (or Apabhransha) poetry was written in the year 769 AD, and by the European Middle Ages it became known as 'Hindvi'. Muslim Turks invaded the Punjab in 1027 and took control of Delhi in 1193. They paved the way for the Islamic Mughal Empire, which ruled northern India from the 16th century until it was defeated by the British Raj in the mid-19th century. It was at this time that the language of this book began to take form, a mixture of Hindvi grammar with Arabic, Persian and Turkish vocabulary. The Muslim speakers of Hindvi began to write in the Arabic script, creating Urdu, while the Hindu population incorporated the new words but continued to write in Devanagari script.

- McGregor, Stuart (2003), "The Progress of Hindi, Part 1", Literary cultures in history: reconstructions from South Asia, p. 912, ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4 in Pollock (2003)

- Ali, Syed Ameer (1989). The Right Hon'ble Syed Ameer Ali: Political Writings. APH Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-81-7024-247-5.

- Hutchinson, John; Smith, Anthony D. (2000). Nationalism: Critical Concepts in Political Science. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-20112-4.

In the nineteenth century in north India, before the extension of the British system of government schools, Urdu was not used in its written form as a medium of instruction in traditional Islamic schools, where Muslim children were taught Persian and Arabic, the traditional languages of Islam and Muslim culture. It was only when the Muslim elites of north India and the British decided that Muslims were backward in education in relation to Hindus and should be encouraged to attend government schools that it was felt necessary to offer Urdu in the Persian-Arabic script as an inducement to Muslims to attend the schools. And it was only after the Hindi-Urdu controversy developed that Urdu, once disdained by Muslim elites in north India and not even taught in the Muslim religious schools in the early nineteenth century, became a symbol of Muslim identity second to Islam itself. A second point revealed by the Hindi-Urdu controversy in north India is how symbols may be used to separate peoples who, in fact, share aspects of culture. It is well known that ordinary Muslims and Hindus alike spoke the same language in the United Provinces in the nineteenth century, namely Hindustani, whether called by that name or whether called Hindi, Urdu, or one of the regional dialects such as Braj or Awadhi. Although a variety of styles of Hindi-Urdu were in use in the nineteenth century among different social classes and status groups, the legal and administrative elites in courts and government offices, Hindus and Muslims alike, used Urdu in the Persian-Arabic script.

- Clyne, Michael (24 May 2012). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-088814-0.

- Clyne, Michael (24 May 2012). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-088814-0.

- King, Christopher Rolland (1999). One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. Oxford University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-19-565112-6.

British language policy both resulted from and contributed to the larger political processes which eventually led to the partition of British India into India and Pakistan, an outcome almost exactly paralleled by the linguistic partition of the Hindi-Urdu continuum into highly Sanskritized Hindi and highly Persianized Urdu.

- Ahmad, Irfan (20 November 2017). Religion as Critique: Islamic Critical Thinking from Mecca to the Marketplace. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-3510-1.

There have been and are many great Hindu poets who wrote in Urdu. And they learned Hinduism by readings its religious texts in Urdu. Gulzar Dehlvi—who nonliterary name is Anand Mohan Zutshi (b. 1926)—is one among many examples.

- "Why did the Quaid make Urdu Pakistan's state language? | ePaper | DAWN.COM". epaper.dawn.com. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Ahmad, Aijazuddin (2009). Geography of the South Asian Subcontinent: A Critical Approach. Concept Publishing Company. p. 119. ISBN 978-81-8069-568-1.

- Raj, Ali (30 April 2017). "The case for Urdu as Pakistan's official language". Herald Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Hakala, Walter (2012). "Languages as a Key to Understanding Afghanistan's Cultures" (PDF). Afghanistan: Multidisciplinary Perspectives.

- Hakala, Walter N. (2012). "Languages as a Key to Understanding Afghanistan's Cultures" (PDF). National Geographic. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

In the 1980s and '90s, at least three million Afghans--mostly Pashtun--fled to Pakistan, where a substantial number spent several years being exposed to Hindi- and Urdu-language media, especially Bollywood films and songs, and beng educated in Urdu-language schools, both of which contributed to the decline of Dari, even among urban Pashtuns.

- Krishnamurthy, Rajeshwari (28 June 2013). "Kabul Diary: Discovering the Indian connection". Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

Most Afghans in Kabul understand and/or speak Hindi, thanks to the popularity of Indian cinema in the country.

- "Who Can Be Pakistani?". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Vanita, R. (2012). Gender, Sex, and the City: Urdu Rekhti Poetry in India, 1780-1870. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-01656-0.

Desexualizing campaigns dovetailed with the attempt to purge Urdu of Sanskrit and Prakrit words at the same time as Hindi literateurs tried to purge Hindi of Persian and Arabic words. The late-nineteenth century politics of Urdu and Hindi, later exacerbated by those of India and Pakistan, had the unfortunate result of certain poets being excised from the canon.

- Zecchini, Laetitia (31 July 2014). Arun Kolatkar and Literary Modernism in India: Moving Lines. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-62356-558-9.

- Rahman, Tariq (2014), Pakistani English (PDF), Quaid-i-Azam University=Islamabad, p. 9, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2014, retrieved 18 October 2014

- Shackle, C. (1990). Hindi and Urdu Since 1800: A Common Reader. Heritage Publishers. ISBN 9788170261629.

- A History of Indian Literature: Struggle for freedom: triumph and tragedy, 1911–1956. Sahitya Akademi. 1991. ISBN 9788179017982.

- Kachru, Braj (2015). Collected Works of Braj B. Kachru: Volume 3. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-3713-5.

The style of Urdu, even in Pakistan, is changing from "high" Urdu to colloquial Urdu (more like Hindustani, which would have pleased M.K. Gandhi).

- Ashmore, Harry S. (1961). Encyclopaedia Britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge, Volume 11. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 579.

The everyday speech of well over 50,000,000 persons of all communities in the north of India and in West Pakistan is the expression of a common language, Hindustani.

- "Statement – 1: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues – 2001". Government of India. 2001. Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ORGI. "Census of India: Comparative speaker's strength of Scheduled Languages-1951, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991 ,2001 and 2011" (PDF).

- "Government of Pakistan: Population by Mother Tongue" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2014.

- "Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex. : SIL International. Online version". Ethnologue.org. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- "Hindustani". Columbia University press. encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- e.g.

- Khan, Abdul Rashid (2001). The All India Muslim Educational Conference: Its Contribution to the Cultural Development of Indian Muslims, 1886-1947. Oxford University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-19-579375-8.

After the conquest of the Deccan, Urdu received the liberal patronage of the courts of Golconda and Bijapur. Consequently, Urdu borrowed words from the local language of Telugu and Marathi as well as from Sanskrit.

- The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 1992. p. 264.

- "Who Can Be Pakistani?". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Rieker, M.; Ali, K. (26 May 2008). Gendering Urban Space in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-61247-1.

- Khan, M. Ilyas (12 September 2015). "Pakistan's confusing move to Urdu". BBC News. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "Why did the Quaid make Urdu Pakistan's state language? | ePaper | DAWN.COM". epaper.dawn.com. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Ahmad, Aijazuddin (2009). Geography of the South Asian Subcontinent: A Critical Approach. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-8069-568-1.

- Raj, Ali (30 April 2017). "The case for Urdu as Pakistan's official language". Herald Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Beaster-Jones, Jayson (9 October 2014). Bollywood Sounds: The Cosmopolitan Mediations of Hindi Film Song. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-999348-2.

- "Urdu newspapers: growing, not dying". asu.thehoot.org. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- Russell, Ralph (1999). "Urdu in India since Independence". Economic and Political Weekly. 34 (1/2): 44–48. JSTOR 4407548.

- "Highest Circulated amongst ABC Member Publications Jan - Jun 2017" (PDF). Audit Bureau of Circulations. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- "Most Pakistanis and Urdu speakers live in this Australian state". SBS Your Language. sbs.com.au.

- "Árabe y urdu aparecen entre las lenguas habituales de Catalunya, creando peligro de guetos". Europapress.es. 29 June 2009. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- Colin P. Masica, The Indo-Aryan languages.

- Khan, Sajjad, Waqas Anwar, Usama Bajwa, and Xuan Wang.

- Aijazuddin Ahmad (2009). Geography of the South Asian Subcontinent: A Critical Approach. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-81-8069-568-1.

- "About Urdu". Afroz Taj (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- Raj, Ali (30 April 2017). "The case for Urdu as Pakistan's official language". Herald Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "Government of Pakistan: Population by Mother Tongue" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2006.

- In the lower courts in Pakistan, despite the proceedings taking place in Urdu, the documents are in English, whereas in the higher courts, i.e. the High Courts and the Supreme Court, both documents and proceedings are in English.

- Rahman, Tariq (2010). Language Policy, Identity and Religion (PDF). Islamabad: Quaid-i-Azam University. p. 59. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Hussain, Faqir (14 July 2015). "Language change". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Wasey, Akhtarul (16 July 2014). "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Roy, Anirban (28 February 2018). "Kamtapuri, Rajbanshi make it to list of official languages in". India Today. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- "The Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2012.

- Clyne, Michael (24 May 2012). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. p. 395. ISBN 978-3-11-088814-0.

- Everaert, Christine (2010). Tracing the Boundaries Between Hindi and Urdu: Lost and Added in Translation Between 20th Century Short Stories. BRILL. p. 225. ISBN 978-90-04-17731-4.

- Clyne, Michael (24 May 2012). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. p. 395. ISBN 978-3-11-088814-0.

- "Urdu Phonetic Inventory" (PDF). Center for Language Engineering. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Masica (1991:110)

- Ohala (1999:102)

- Ahmad, Aijaz (2002). Lineages of the Present: Ideology and Politics in Contemporary South Asia. Verso. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-85984-358-1.

On this there are far more reliable statistics than those on population. Farhang-e-Asafiya is by general agreement the most reliable Urdu dictionary. It was compiled in the late nineteenth century by an Indian scholar little exposed to British or Orientalist scholarship. The lexicographer in question, Syed Ahmed Dehlavi, had no desire to sunder Urdu's relationship with Farsi, as is evident even from the title of his dictionary. He estimates that roughly 75 per cent of the total stock of 55,000 Urdu words that he compiled in his dictionary are derived from Sanskrit and Prakrit, and that the entire stock of the base words of the language, without exception, are derived from these sources. What distinguishes Urdu from a great many other Indian languauges … is that it draws almost a quarter of its vocabulary from language communities to the west of India, such as Farsi, Turkish, and Tajik. Most of the little it takes from Arabic has not come directly but through Farsi.

- Dalmia, Vasudha (31 July 2017). Hindu Pasts: Women, Religion, Histories. SUNY Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-1-4384-6807-5.

On the issue of vocabulary, Ahmad goes on to cite Syed Ahmad Dehlavi as he set about to compile the Farhang-e-Asafiya, an Urdu dictionary, in the late nineteenth century. Syed Ahmad 'had no desire to sunder Urdu's relationship with Farsi, as is evident from the title of his dictionary. He estimates that roughly 75 percent of the total stock of 55.000 Urdu words that he compiled in his dictionary are derived from Sanskrit and Prakrit, and that the entire stock of the base words of the language, without exception, are from these sources' (2000: 112–13). As Ahmad points out, Syed Ahmad, as a member of Delhi's aristocratic elite, had a clear bias towards Persian and Arabic. His estimate of the percentage of Prakitic words in Urdu should therefore be considered more conservative than not. The actual proportion of Prakitic words in everyday language would clearly be much higher.

- Taj, Afroz (1997). "About Hindi-Urdu". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Urdu's origin: it's not a "camp language"". dawn.com. 17 December 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

Urdu nouns and adjective can have a variety of origins, such as Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Pushtu and even Portuguese, but ninety-nine per cent of Urdu verbs have their roots in Sanskrit/Prakrit. So it is an Indo-Aryan language which is a branch of Indo-Iranian family, which in turn is a branch of Indo-European family of languages. According to Dr Gian Chand Jain, Indo-Aryan languages had three phases of evolution beginning around 1,500 BC and passing through the stages of Vedic Sanskrit, classical Sanskrit and Pali. They developed into Prakrit and Apbhransh, which served as the basis for the formation of later local dialects.

- "Urdu's origin: it's not a "camp language"". dawn.com. 17 December 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

Urdu nouns and adjective can have a variety of origins, such as Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Pushtu and even Portuguese, but ninety-nine per cent of Urdu verbs have their roots in Sanskrit/Prakrit. So it is an Indo-Aryan language which is a branch of Indo-Iranian family, which in turn is a branch of Indo-European family of languages. According to Dr Gian Chand Jain, Indo-Aryan languages had three phases of evolution beginning around 1,500 BC and passing through the stages of Vedic Sanskrit, classical Sanskrit and Pali. They developed into Prakrit and Apbhransh, which served as the basis for the formation of later local dialects.

- Ahmad, Aijaz (2002). Lineages of the Present: Ideology and Politics in Contemporary South Asia. Verso. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-85984-358-1.

On this there are far more reliable statistics than those on population. Farhang-e-Asafiya is by general agreement the most reliable Urdu dictionary. It was compiled in the late nineteenth century by an Indian scholar little exposed to British or Orientalist scholarship. The lexicographer in question, Syed Ahmed Dehlavi, had no desire to sunder Urdu's relationship with Farsi, as is evident even from the title of his dictionary. He estimates that roughly 75 per cent of the total stock of 55,000 Urdu words that he compiled in his dictionary are derived from Sanskrit and Prakrit, and that the entire stock of the base words of the language, without exception, are derived from these sources. What distinguishes Urdu from a great many other Indian languauges … is that it draws almost a quarter of its vocabulary from language communities to the west of India, such as Farsi, Turkish, and Tajik. Most of the little it takes from Arabic has not come directly but through Farsi.

- Dalmia, Vasudha (31 July 2017). Hindu Pasts: Women, Religion, Histories. SUNY Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-1-4384-6807-5.

On the issue of vocabulary, Ahmad goes on to cite Syed Ahmad Dehlavi as he set about to compile the Farhang-e-Asafiya, an Urdu dictionary, in the late nineteenth century. Syed Ahmad 'had no desire to sunder Urdu's relationship with Farsi, as is evident from the title of his dictionary. He estimates that roughly 75 percent of the total stock of 55.000 Urdu words that he compiled in his dictionary are derived from Sanskrit and Prakrit, and that the entire stock of the base words of the language, without exception, are from these sources' (2000: 112–13). As Ahmad points out, Syed Ahmad, as a member of Delhi's aristocratic elite, had a clear bias towards Persian and Arabic. His estimate of the percentage of Prakitic words in Urdu should therefore be considered more conservative than not. The actual proportion of Prakitic words in everyday language would clearly be much higher.

- Taj, Afroz (1997). "About Hindi-Urdu". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Khan, Iqtidar Husain (1989). Studies in Contrastive Analysis. The Department of Linguistics of Aligarh Muslim University. p. 5.

It is estimated that almost 25% of the Urdu vocabulary consists of words which are of Persian and Arabic origin.

- American Universities Field Staff (1966). Reports Service: South Asia series. American Universities Field Staff. p. 43.

The Urdu vocabulary is about 30% Persian.

- Versteegh, Kees; Versteegh, C. H. M. (1997). The Arabic Language. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11152-2.

... of the Qufdn; many Arabic loanwords in the indigenous languages, as in Urdu and Indonesian, were introduced mainly through the medium of Persian.

- Taj, Afroz (1997). "About Hindi-Urdu". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- http://www.iranchamber.com/literature/articles/language_of_armies.php

- Ahmad, Rizwan (2011). "Urdu in Devanagari: Shifting orthographic practices and Muslim identity in Delhi". Language in Society. Cambridge University Press. 40 (3): 259–284. doi:10.1017/S0047404511000182. hdl:10576/10736. JSTOR 23011824.

- Das, Sisir Kumar (2005). History of Indian Literature: 1911–1956, struggle for freedom: triumph and tragedy. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 9788172017989.

Professor Gopi Chand Narang points out that the trends towards Persianization in Urdu is not a new phenomenon. It started with the Delhi school of poets in the eighteenth century in the name of standardization (meyar-bandi). It further tilted towards Arabo-Persian influences, writes Narang, with the rise of Iqbal. 'The diction of Faiz Ahmad Faiz who came into prominence after the death of Iqbal is also marked by Persianization; so it is the diction of N.M. Rashid, who popularised free verse in Urdu poetry. Rashid's language is clearly marked by fresh Iranian influences as compared to another trend-setter, Meeraji. Meeraji is on the other extreme because he used Hindized Urdu.'

- Shackle, C. (1 January 1990). Hindi and Urdu Since 1800: A Common Reader. Heritage Publishers. ISBN 9788170261629.

- Kaye, Alan S. (30 June 1997). Phonologies of Asia and Africa: (including the Caucasus). Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-019-4.

- Patel, Aakar (6 January 2013). "Kids have it right: boundaries of Urdu and Hindi are blurred". Firstpost. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Gangan, Surendra (30 November 2011). "In Pakistan, Hindi flows smoothly into Urdu". DNA India. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

That Bollywood and Hindi television daily soaps are a hit in Pakistan is no news. So, it's hardly surprising that the Urdu-speaking population picks up and uses Hindi, even the tapori lingo, in its everyday interaction. "The trend became popular a few years ago after Hindi films were officially allowed to be released in Pakistan," said Rafia Taj, head of the mass communication department, University of Karachi. "I don't think it's a threat to our language, as it is bound to happen in the globalisation era. It is anytime better than the attack of western slangs on our language," she added.

- Clyne, Michael (24 May 2012). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-088814-0.

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (26 July 2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- Ahmad, Aijaz (2002). Lineages of the Present: Ideology and Politics in Contemporary South Asia. Verso. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-85984-358-1.